Michael Shellenberger talks with Nick O’Malley, National Editor of Climate and the Environment, Sydney Morning Herald

This is a near-verbatim transcript. No substantive changes were made. All editor’s notes are [in brackets] and offered only for clarity.

Michael: That's fine. I'm happy to answer any questions you want. Any question you ask is fine. I've even got the book here. You may if you ask about a specific thing, I'm going to look it up and make sure I remember just right to get it just right.

Nick: So the reason why I was prompted to contact you is that like anyone who reads in this field, your views run against those of most of my sources. So, the main one I suppose that caught my attention was “Climate Change is Not Making Natural Disasters” and everywhere I look, trying to approach it from your perspective, I just find it a confounding thing for you to assert. So let's go to that.

Michael: Okay. So you say something or do you want to ask us a more specific question?

Nick: No, no, why don't you jump in?

Michael: So the IPCC you know, United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on climate change defines disasters very specifically, it's not talking about weather events. It's talking about the impact of weather extremes weather events, on people and property. It's very, very clear about this in the IPCC and their definitions. So and what we know is that deaths from natural disasters have declined 90% over the last hundred years, they've declined 80% of the last 40 years, they declined during a period of significant population growth. So the population has quadrupled since over the last hundred years. So that 90% decline is even larger than it may seem. Now in terms of property...

Nick: So good. Can I interrupt for a second? Though you didn't say that in the piece, in the piece you just said, it's not making disasters worse, but you're going by the IPCC definition. So correct me if I'm wrong. So that is to say, you're not asserting that disasters are becoming more common and more intense or weather related disasters are becoming more common or more intense, but that their impact on communities is not; is that the difference?

Michael: The differences, okay, and this is very important.

A hurricane by itself is not a disaster. If a hurricane doesn't hurt anybody, if it doesn't kill anybody, if it doesn't hit landfall, or whatever. If it doesn't cause any damage, it's not a disaster. It's only a disaster when it kills people or destroys property. That's how the IPCC defines it.

Now, in my arguments with Climate Feedback and others on Twitter last few days, some people say things they do this they go, they go, “Michael says that climate change is not increasing natural disasters. He's wrong. Look at these weather extremes. Look at these extreme weather events.” And they say things like, “Increasing severity of some hurricanes, longer fire season,” all of which is in this very long, thick 400 page book [Apocalypse Never] in great detail.

And in what I'll underscore is one thing, every single scientific claim I made for this book I made before publishing the book, as it relates to climate change, and the scientists reviewed it. So on each of these things, they've all seen it, they've all reviewed it, this is very well understood.

Now in terms of property damage, —

Nick: To my satisfaction, I haven't cleared that up. So you're not asserting that the more extreme weather events are not happening. I'm not to some extent related to anthropogenic climate change. You're asserting that the impact on communities is decreasing.

Michael: Definitely

Nick: Okay, so anthropogenic climate change is generating more extremes and whether there's some of which are defined by some if not the IPCC is disasters.

Michael: Again, they're only disasters when they cause —

Nick: Yeah, I get the point.

Michael: I think you said what I think so in terms of cost.

Nick: So you accept that there's more extreme weather because of climate change.

Michael: Yeah. On some. Basically, my critics and the people that I'm arguing with on Twitter and elsewhere, when they cite cases of say, more intense hurricanes, longer fire season more heat waves, yes, hundred percent, because they're just drawing on the same science I am. Totally agree. That's not the same thing as disasters and it's really important because disasters are not extreme weather events.

In other words, so one, I think one question that we'll have is do we expect this long decline in deaths to reverse itself. That's what you would worry about. Right? So let's say we got more severe hurricanes; is it going to reverse itself? Because I think everybody wants to know, right? It's hard to see a scenario where that number reverses itself in some significant way. In other words, the difference in terms of disaster preparedness and infrastructure is huge compared to the intensity of the increase of these different weather events or extreme events.

Nick: And you think, you know, an overreaction due to climate alarmism.

Michael: What's that?

Nick: And do you think that the amount of resources we're putting into this is an overreaction in part due to climate alarmism?

Michael: I've never said that.

Nick: Okay.

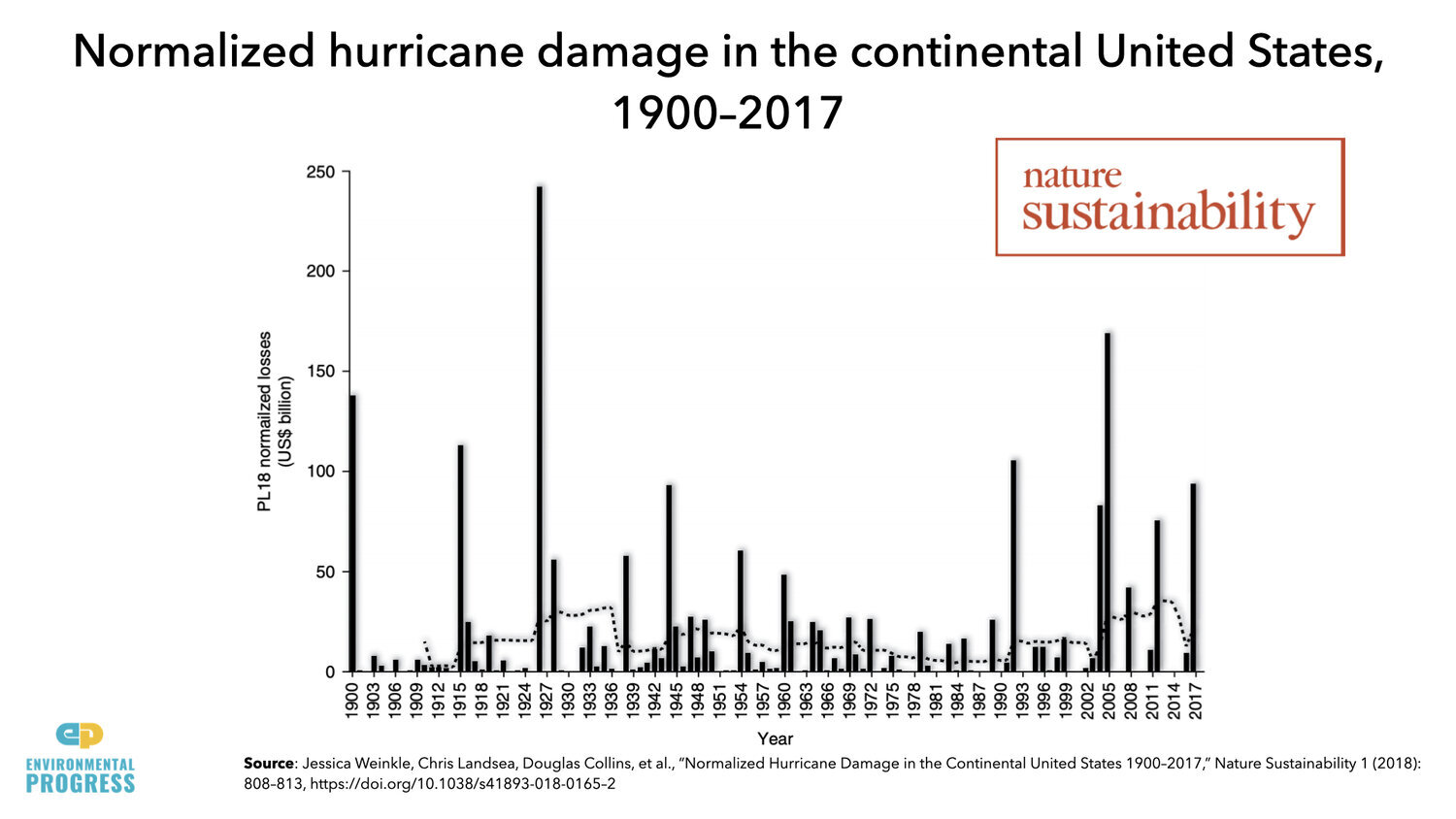

When rising wealth through development is accounted for, there is no increase in the cost of natural disasters.

Michael: That's not my view. I think too much money is being put into renewables but that's because I think renewables are terrible source of energy.

It's easy, I think, to see me saying these different things and then kind of want to map onto me things that other people you might imagine

Nick: — would be that could be the case. Yeah. So.

Michael: So just to kind of finish the point, I mean, you know, these big declines in deaths from, say, cyclones in Bangladesh or the South Indian sea, you know, these are our reductions, mostly from better weather prediction, and some storm shelters.

Well, do we think cyclones are gonna be so much more intense that they wipe out those significant declines and deaths? Hard to see it. I mean, that's not to say we shouldn't worry about climate change. I think we should. It's not to say that we shouldn't do anything about climate change. I think we should. But I think that we have to have people understand, a) Climate change is not increasing natural disasters, because natural disasters are not getting worse. They're getting better, in the sense of more lives are being saved.

Now, in terms of cost, when you normalize the cost, there's no trend, including on the two big ones, hurricanes and floods, but certainly, with all of them, there's no trend.

Nick: I want to put this because I've seen your exchange with Climate Feedback. When I put this to a couple of sources in Australia, they said “Look, focusing on the definition by the IPCC to defend this position” — these are my words, not my sources — but the implication is that they found it to be intellectually dishonest.

Michael: Why? To rely on the IPCC definition is intellectually dishonest, why?

Nick: No, they're just focusing on the definition. Because they pointed out that the IPCC uses a definition, different institutions around the world use different definitions. The governor of Florida uses a definition, the governments of New South Wales in Australia use different definitions. So to focus on this to assert that there are less disasters or fewer disasters is misleading, certainly misleading to readers of East Australia, because they saw us say natural disasters aren't getting worse; the implication of that? Surely you can see that the implication to a reader of that is that it is your assertion that there are fewer extreme weather events.

Michael: No, absolutely not. That's just a — sorry, but you kind of go you make it sounds like some semantic thing. There's a difference between a hurricane and —

More wood fuel and more housing near forests, not climate change, explains more frequent and more intense fires in Australia and California.

Nick: — many of your readers that I have spoken to view it as a semantic argument on your behalf.

Michael: I mean, that's bizarre to me. In other words, here are these people accusing me of actually saying something different than the IPCC. And here I say, “Here's what the IPCC says,” and now I’m, “Being semantic”?

Nick: You said natural disasters are not getting worse due to climate change. And by any scientific measure, they are but you'll you'll notice —

Michael: No! I'm sorry, but by what scientific measures are disasters getting worse? Which one?

Nick: I spent the morning reading them when I was determined not to get into my pile of papers next to yours, but it is not hard to find any measure, as you would know better than me. In the past couple of years [IPCC] Myles Allan has led this, this new science of attributing individual or more narrow accounting impacting climate change and disasters. This is not, it's not a couple of people.

Michael: No, no. First of all, you just conflated extreme weather with disasters. So you're just doing it right there. I'm not actually bringing any fault with those attribution studies. I accept the attribution studies. And in fact, in my book, I go into great detail. In fact, I mean, that's the whole point is I'm kind of like I'm actually the chapter and one of the headlines, one of the section descriptions is, "A Small Part of Bigger Problems", I think is what it's called.

But basically, it's not to say that it's not saying climate change isn't happening. It's not to say that climate change isn't making some weather events more extreme. I think it is. It is to say that it's not making disasters worse. How could it? Disasters are not getting worse! Disasters are getting better: There's fewer deaths and no increase in damage. How can that not be anything other than we should be hallelujahing, that fewer people die of disasters every year!

Nick: We should. I looked at an obvious areas I was slightly more familiar with and I have very little of your expertise. So I looked at your sections on the most recent Australian bushfires.

So you say that the 2020 fires burned half as much as the 2002 fires. I checked those figures and the figures that I can see the public figures in Australia are that in 2020, 18 million hectares burned, and in 2002 21 million. So half is just not correct. You also cite

Michael: Are you gonna let me respond or no? So I may go. Alright, I'm going to find the source. All right, so our sources are: LS et. al. National Inquiry and Bushfire Mitigation Management University. The final report summary Victorian Brushfires Royal Commission, Black Friday Bushfires, Australian Institute for Disaster Resilience.

Nick: I've got to check them and see where the discrepancy is. Yeah, it's possible. I'm wrong. It's possible. You are it's possible they are.

Michael: I'm actually fine by the way to do that's actually fine to do over email if you want. That's totally fine.

Nick: Okay, good. And on that process, looking at that the emphasis that you put on certain facts, which is fine for someone in engaged in a debate, that's absolutely fine. But I found some bits that I disagreed with having those watch most of the Royal Commission into bushfires. You noted the number of deaths, and they were, thankfully, very low. I think you said three or four. I've got no problem with that figure.

What I found remarkable though, is, that that doesn't count the 400 deaths that have been attributed to the pool of smoke that lingered over Australian cities. And that number is expected to rise. And this again is, it might be data you're not yet aware of because it came up in the Royal Commission. And it doesn't.

And it almost dismisses, I think you say that there's an undue focus on that smoker perhaps, and hysteria. I don't know if that's the word you use. But that was how I read it among Australian media as a result of the smoke that lingered over populated areas. But I would say that that smoke had a real impact on people's lives. And we know it had a real impact on deaths, that then some either really significant things to sort of shoot past. And I think it is to underestimate. I think it is to underestimate the impact of the fires. I don't think it's necessarily deliberate, but I think that's the result.

[O’Malley appears to be referring to this sentence from Apocalypse Never: “Climate alarmism, animus among environmental journalists toward the current Australian government, and smoke that was unusually visible to densely populated areas, appear to be the reasons for exaggerated media coverage.”]

Michael: Yeah, well, let me tell you what I want to say about it. I don't want to do that. Much of this book is a criticism of wood burning for the smoke impacts on people's lives. I cite the deaths from burning and breathing smoke. So I'm not minimizing it. I also live in California and we had a very bad smoky fire season and we don't like it.

Here's one thing I will say though, I think it's important here. One of the reasons for the failure to burn up the underbrush or the wood fuel that accumulates in managed forests, the post-European forests is because the locals don't like all the smoke, you know? And, and I appreciate it! I don't want smoke! When one of our neighbors here — in our natural gas burning neighborhood — burns wood, everyone's like, “What are you doing? You're burning wood! It's terrible!” So I don't know I don't want to do that.

But I do want to just kind of note like, you know, you might be in a situation too, where, where you're actually doing what we need to do or what you guys need to do to burn up that that wood fuel and you still have smoke, you know?

And it really and it could kill people and it could harm people. I mean, it's challenging to measure specific events like that. But I don't mean to do that, and you know, look, we did say, we did go through the fatalities. You know, if I felt like there was some good study, and maybe you have it that tries to attribute the number of deaths from those fires. I think it's tricky, again, because you'd have to somehow calculate how many more deaths that is from that smoke inhalation, from properly managed burns.

Nick: If it's something interesting you were and I'll happily flick it to you. Okay. There's also very good science in Australia, suggesting that the buildup of wood is not the cause of these of the increasing scale and intensity of these fires. The person I cite there is Linden Meyer, who I'm happy to send to you.

Michael: Okay, and I cite one scientist estimates there's 10 times more wood fuel in Australia's forests today than when Europeans arrived. The main reason is that the government of Australia, as in California, refused to control burns for both environmental and health reasons. As such fires would have occurred even had Australia's climate not warmed.

That's David Packham interviewed by Andrew Boldt. Is David Packham, someone you know?

Nick: I do know him. Andrew Bolton. I know he has very strong views on these issues, views that are rejected by every emergency service and government in the country, who say, in fact, we do keep up with hazard reduction burns, and we do support hazard reduction burns, they're getting harder to conduct safely in a hotter, drier climate. And that's for obvious reasons.

You know, they've got a short window during the middle of the year where they can conduct these burns in Australia safely. And that window is shrinking. There is no government that I am aware of, and there is no agency of the government that I'm aware of that advocates against hazard reduction burning. But it is a view of some people that that are that somehow green activists have infected the policymaking process.

Michael: That's not what I'm claiming.

Nick: I know what you're saying at all. But it is part of a broader debate. And I wouldn't pretend for a second that you'd said that. More broadly; what about the response from Climate Feedback? Are you concerned that a researcher and six, from from my reading of it reasonably prominent qualified academics have come out to respond to your piece like that?

Michael: Oh, no, I'm delighted, because they just, absolutely. I mean, it was embarrassing for them. I mean, they're endorsing the Sixth Mass Extinction claim? I mean, when I saw that, I was like, wow. Also, the author —

Nick O: — I haven't done enough reading to discuss.

Michael: Yeah, I mean, I'll just say it.

You always kind of go, “Wow, they're so impressive scientists.” Well, that scientist that makes that claim? That claim was considered to be used in the IBPES review, which came out last year, and I interviewed the co-chair of IPBES, and he and they specifically rejected it, because we're not in a Sixth Mass Extinction. So for me, that's that.

And then the other issue is the disasters, and that issue is just they're using what they're doing consistently; if they're actually saying, “Michael,” they go, “Michael's wrong by saying that climate change isn't making natural disasters worse, look at these extreme weather events.”

I mean, you've got to admit, Nick, that's misleading to do that.

Nick: Well, no, I do take their point of view and the point of view of others that have been put to me that, in fact, to make the assertion in a newspaper, in particular, without context that climate change is not making natural disasters worse.

Michael: It's true, how could you say —

Nick: But you say to me, but in conversation and you support your book that you're using the language the way the IPCC does, but it's not the way humans speak.

I mean, if I was to say, if I was to say to somebody, natural disasters are getting better, the presumption is that I'm trying to assert that there are fewer bushfires, fewer droughts, fewer floods, less intense hurricanes, and that's clearly not true.

Michael: But Nick, I mean seriously though, my critics should choose. Are they going to criticize me for not being true to the science? Or are they going to criticize me for being too true to the science — and not true enough to like, well “believe”?

I mean, I wrote, I slaved on this thing with all the footnotes precisely so people can understand exactly what I was claiming. Every claim in that article is sourced back here. And yeah, so if someone wants to criticize me, for using the IPCC definition of disasters, Boy, have at it. I'm happy to be criticized for that.

Nick: Well, now you're gonna submit a semantic change.

Michael: But the suggestion that it's a distinction without a difference is outrageous!

Nick: So what about the other assertions raised in, in the climate feedback, critique of your piece?

Michael: Well, let's go through, I mean, I'm happy to go through them. Do you want to just give me another one? I read a long response. As you probably saw,

Nick: I thought if there was anything particularly wanted to bring on

Michael: Well, [the responses are] terrible. I mean, one of them. This guy goes, this guy said, I did the whaling the whale oil story wrong. It's it's hilarious because our whaling — What's that?

Nick: I wouldn't argue with that, but I thought you brought the whale oil up.

Michael: Yeah, but he sort of suggested that I was wrong about it. Of course he didn't present any evidence, but he really... I mean, what happens is, there's some arrogance here where these guys they actually haven't done the research, but because they have PhDs and I'm just a journalist, they kind of go, “Well, I'm gonna go and opine” — on stuff they've never even looked at!

There was a renewables claim where a person claimed that solar and wind only require three to five times more land than natural gas or nuclear plants. Hilarious! Just go on Google Maps, you can draw around a power plant, any power plant in the world, solar, wind, nuclear, gas, whatever, just draw around it. And then you have the power density calculation. You just need to divide that into the amount of electricity it produces every year, and you can compare them and what you'll find is it's always two orders of magnitude larger.

For solar and wind farms, it's usually between 300 and 400 times, so to suggest is three or four times is completely outside the mainstream. The book that you know, and one thing I did know, Nick, and —

Nick: — Did you not assert that you'd need to use the entire planet's land surface area to —

Michael: — I did not say that.

Nick: You didn't?

Michael: No. I just want to make one quick point, which is that I wanted to be able to go out and talk to people like you and say, “I am using either the best-available peer-reviewed research, or the best available academic publishing or whatever, and not my own.”

We do all these calculations, power density calculations, on our own, all the time. I relied on Vaclav Smil, who Bill Gates says is the person whose books he most waits for is most respected; Vaclav Smil, by the way, I don't agree with Vaclav [on everything]. He's a Malthusian. I love the guy, nice guy. But he's actually respected by liberals, conservatives, moderates, everybody, and I relied on him [for power density calculations].

Nick: I wasn't arguing with you about energy density and renewables. It's an obvious point. but I'm not sure about the land size assertions. And I think that's one of the reasons why people are so interested in hydrogen because it's potential density. But —

Michael: — I am I am with you on hydrogen. I'm agnostic of whether cars will be hydrogen or electricity, but doesn't really matter.

Nick: Yeah. Um, the common thread I get when I interview people about you and your work over the years though, is that they say that you

Michael: Over the years? Wow.

Nick: No, no my research people who have been reading your work over the years. Not mine at all. No, but they say that they find in your writing and in your arguments you cherry pick after and you conflate, and that many of your assertions are true and many and not, and it appears to them as be part of deliberate advocacy. Is that a reasonable criticism?

Michael: No. What that is is psychological projection. That's what they're doing and they're revealing to you by projecting it onto me. And I gave you one example, the sleight of hand of mixing people up. It's the conflation. They're conflating extreme events and disasters.

And it sounds like you want to let them off the hook. I don't want to they should never.

Nick: I don't think, as I said, I don't think people speak like that. I think to most people reading your piece where you assert climate change is not making natural disasters worse; well first, they would misunderstand what you're saying. If you're saying that you are, you're referring to the IPCC definition of disaster as impact on communities. That is not how people would hear that.

Michael: I don't agree, Nick. Because look, when the media cover a disaster, they're covering a disaster. They're not covering the weather event. And when a hurricane doesn't touch ground; I mean, it makes some media coverage; but it doesn't make nearly as much media coverage when it touches down.

So I think what's going on is that we've had the news media for 30 years suggesting that disasters are getting worse, and they're getting worse because of climate change, and I think that people have been misled badly. Wouldn't you agree? Because deaths are so far down?

Michael I mean, this is this incredible story. death tolls have declined. I mean, I would suggest, I mean, let me ask you: If I went to interview readers at Sydney Morning Herald and I was like, do you think that deaths from disasters have gone up or down over the last 40 years? What do you think they would say?

Nick: They’d probably say, up, I would guess.

Michael: And whose fault is that?

Nick: Well, I shouldn't be attributing fault until I've researched the data.

Michael: But your job is to kind of educate the public about environmental issues. And they think that —

Nick: It's just why conducts interviews like it we're being diverted I think down a cul de sac here.

You said I made a bunch of allegations against you. I simply didn't. I put questions to you based on interviews that I've conducted which you know is my job.

Michael: I mean, the more like the question about the Robert Mercer? You're literally going to quote some guy just making pulling shit out of his ass? You can quote me Will Stephen lying about me, making shit up? Robert Mercer? I mean, it's fine. Like, this guy is tying me to Trump or something. It's ridiculous.

Nick: But you can't criticize it.

Michael: Literally like you call him up and he goes — because he thinks everybody who disagrees with him is some Trump-supporter — “He’s some right-winger.” I'm a life-long Democrat and he said you might be getting funding from Mercer? What because what, because you don't like me and you don't like Mercer? I mean, he's supposed to be a scientist. And he's making an allegation that I'm taking money from one of Trump’s main financiers. And I'm supposed to be like, “Oh, yeah, no big deal, Nick,” to be accused of total bullshit like that?

Nick: No one has written a word about you here. It is perfectly normal to test ideas and test claims.

Michael: Oh come on, Nick. I mean, that's like, I mean, that'd be like, your whole line of questioning. Anyway, I'm not supposed to say it because it's the famous you know.

Look, I'm so happy that you're actually talking to me on a video conference and that we're having this. So I'm grateful. So I'm not — I don't want to maybe you're mad at what I said to you, and if so, all I can know that I don't think you should be. This is the time for you to ask me any nasty questions I can answer. I will answer. You can ask me anything you want.

Nick: The description of you as a nuclear lobbyist is false.

Michael: I'm not a lobbyist.

Nick: Right. Do you take any funding from anyone advocating for you?

Michael: Absolutely not. Never have never will. And I've suffered pretty significantly if you would look at my budget, just so you know. Most big environmental groups United States who take money directly from people that made their money in fossil fuels have budgets around 100 million a year, my budget is less than a million. And we've lost donors because we haven't towed the party line on a whole set of issues. The controversial positions I've taken over the last 15 years of my career, every time I've made a controversial position, I've lost donors, not for any financial reason, because they don't like the discomfort of disagreeing with environmentalists.

And so then I go through that experience. And then my whole thing is like, everyone's like, “So Michael, tell us who's the money you're taking from,” or whatever, and I'm like, “I put my donors” — by the way, Climate Feedback does not list where their donors are from, it does no say who their board of directors is, there is no appeal process — “I list my donors on my website. I've always done that. And I list the donors in the book.

And so when people say, like, “Who are you taking your money from?” I'm like, “How much more do I have to do? Like, do we put it in every tweet? It's in like the book and on the website on the About page! I mean, and if you actually were to research them, you would discover that three of them are billionaires. It’s not like — I mean, and they could give me a lot more money if they wanted to — it's fine. philanthropy in the United States is totally super-charged, it's on steroids. But I mean, you have to understand these NGOs in the United States, because we have the inheritance tax traditionally. You know, that's why you have these big foundations and stuff. There's so much money for environmental advocacy when it fits the, you know, the status quo view of 100% renewables and climate change is going to kill all of our kids.

When you actually get out of that you say something different, you actually get punished financially. That's what I wrote about in my article, I've had it happen to me more than once, Twice to be specific. Becoming pro-nuclear was not a great — if I was looking to make a lot of money that wouldn't have been what I'd chosen.

Nick: Okay. Point taken. Was your way into this intellectually? Wasn't nuclear was your decision some years ago that you've written about elsewhere, that you'd been misled about nuclear and you the way I understand it, that nuclear power was the fastest and best way for us to decarbonize the economy while providing enough power and sustaining economies. Was that the door open for you into the rest of this?

Michael: No. I mean, it's really there's a much longer history — maybe boring — over the last 15 years. I mean, I see this book as a bookend to this essay I wrote in 2004, I co-authored, called “The Death of Environmentalism.” And I would identify a couple of important phases. The first was with Death of Environmentalism and the new Apollo project that sort of inspired that essay. That was the original Green New Deal. It's the one that I advocated the Obama team to add to do a big green stimulus package.

Nick: With a nuclear focus and so forth, No?

Michael: No. I was only coming slowly to pro-nuclear in 2009. I changed my mind because I was inspired by Stewart Brand and I sat down, I read the World Health Organization reports on Chernobyl, and then we were just having a whole bunch of problems with renewables.

And there was a period of time where I was like, “Oh, we should have nuclear and renewables!” And then you're kind of like, “So if we have nuclear, do we need renewables?” Well, obviously not because France doesn't need renewables if it's 75%. Nuclear, it doesn't need In fact, when it added wind, it had to add gas. So it could deal with these huge variations and the carbon intensity of French electricity increased, which I note in the book.

So the idea that you needed renewables is entirely based on the idea that we should not, or could not have nuclear. And then I said — this was 2010, I came out as pro-nuclear, which was great timing because Fukushima happened next year, so just a bit for popularity — and then I decided to campaign for nuclear in 2016, because nuclear plants were being closed, mostly for political reasons, you know, and yes, there's cheap gas.

Nick: Well, they're not also aging by them.

Michael: No. Well, I mean, they're obviously older than they were, but nuclear plants, first of all, the sites themselves are basically for me, as someone who worries about climate change. I know you probably don't believe that, but as somebody that would actually like to —

Nick: — Of course I believe that.

Michael: Okay, all right, sorry. Um, I would like to decarbonize all of our energy. Me, I would like to decarbonize all the world's energy. I think the fastest, cheapest, simplest way to do is with nuclear energy. By far, those plants, those sites are so hard, you can't get sites now, to build nuclear plants in the United States, you just get too much opposition. So those sites often have like one or two reactors on them could be places that could have six reactors, could produce hydrogen can produce huge amounts of electricity, and electrify the grid. So for me saving those plants, and then you go, Okay, how long can a nuclear plant operate? Well, in the United States, they just have announced that they can run for 80 years, you know, and

Nick: The one that they made that announcement for 80 years, could be inundated by sea level rise far sooner than that, surely that's a concern.

Michael: Well, I mean, what — do you think we're helpless to sea level rise?

Nick: I mean, it's something to think about when you're advocating an idea, like, lifespan for nuclear power.

Michael: No, I mean, look, I mean, have you been to Venice or Netherlands?

I mean, you go to Venice. And they have a huge sea wall that floats up. I mean, the idea that we're sort of like, “Oh my god,” you know,” 0.6 meters of sea-level rise — we're helpless against that!”

I mean, come on dude. Like, I mean, you can solve that problem. That's not a huge problem and most places are much farther above sea level than a half a meter.

And you know, look all the parts of the nuclear plant can be replaced almost all of them sorry, almost all of them steam generators, turbines, you know, when you get to the reactor vessel itself, okay, some point you probably have to replace that reactor vessel, we don't know it could be 80 years, it could be 100 years. You can use science to look at the reactor vessel, we can do science and figure out if it needs to —

Nick: — Mycle Schneider. I guess that one of the main problems with nuclear apart from its incredible cost is the fact that as, the fleet ages and it needs to be as elemental, it needs to be replaced and repaired. It becomes far less reliable. I think he says the the French nuclear fleet is offline for about 80 days a year.

Michael: He's so misleading. That's so deliberately misleading because he — I know that he understands what's going on in France. And that's not what's going on. So the record on nuclear is actually really clear. First of all, like any new technology, it took a while for these guys to figure out how to properly run these plants. So they were running like 50-60% of the year when Three Mile Island happened in 1979. After that, the industry took measures the government took measures in some ways it sounds weird, but Three Mile Island was great. The nuclear industry, they improved performance, it was often human factors, not fancy machines. And then they took the average capacity factor up to like 92%, I think is what it was last year. The best way for nuclear plants to run is run them full out the other 8% of the year is when they're refueling or doing maintenance.

Okay, okay what what Schneider is referring to, is that France has so much nuclear that in order to deal with the difference in the seasonal loads, they operate their nuclear plants at much lower capacity factors. It's a function of French nuclear success, not nuclear failure that the plants are getting ripped off.

Nick: Could you repeat that last bit?

Michael. So France is 75%, nuclear more or less, Yeah, a little bit less. So in order to so and as it's 20%, as our electricity isn't clear, and so in order for the French grid, because it's some seasons — I assume summer is more high air conditioning although I may be wrong, it might be winter — but one of those seasons, don't quote me which, is a much higher demand than the other seasons. So it means that if you're a heavy nuclear, you just are going to run at lower capacity factors, because you are going to have a big part of the year where you just need to have nuclear plants offline. And that's when they're refueling, you know, doing maintenance —

Nick: Okay so since you began your nuclear advocacy, the cost, the levelized cost of nuclear energy has continued to rise as far as I can see, and the cost of renewables has fallen. Does that challenge any of your assumptions?

Michael: It's not true. I mean,I think you have to avoid cherry picking. You need to choose country level analyses over time. So you're not being like, “Oh, this one solar farm does this,” or “This one nuclear plant” — whatever. That's what Schneider does, and it's misleading.

France and Germany, right next to each other, are two huge economies. In this big experiment, France is sticking with mostly, it's actually not totally, but mostly nuclear. Germany is phasing out nuclear and phasing up renewables. Germany's carbon intensity of its electricity is 10 times higher than France. 10 times! It's amazing. So Germans are 10 times more climate villains than the French on electricity. The Germans spent 1.7 times more for electricity than the French.

Nick: Is that not higher at the moment as it decommissioned from nuclear and transitions to other sources?

Michael: Well, no, I mean, it's so the German electricity costs have increased like 50%. There's they're set to spend $580 billion. I mean, nobody disagrees that Germans have some of the most expensive electricity in Europe and that it's because of the Energiewende. Now, can we easily disentangle how much of that is renewables and how much of it is the nuclear phase-out? No, we can't. But we know that in California, our electricity prices are --

Nick: We know when you rebuild the grid, it means higher costs. But you know, that's why we talk about Levelized cost of power. And that is what Germany is doing.

Michael: Yeah, but so what so the high cost of solar and wind I mean, there's multiple reasons it's obviously much larger land requirements, much larger material throughput, 17 times more material throughput for solar than nuclear, but the big factor is the unreliability. So the University of Chicago hiring a former Obama Administration economist Michael Greenstone did an analysis and found that states that did in the United States, states that did a lot of renewables and have renewable portfolio standard saw very significant cost increases compared to states that didn't. And it's because the cost of managing all that unreliability is very high. I mean, the same thing is happening in Australia.

Nick: So slowly rebuild the grid.

Michael: Well, I mean, rebuild. I mean, just consider that the trend in energy and food and everything else in our lives has been towards dematerialization, over 200 years. The energy we use is less material intensive. I mean, these things these cell phones, you know, they are they've massively dematerialized and that's been great for the environment. It's amazing. You're substituting energy for material for matter. You’re associating energy for nature, similar with plastic, by the way, you're substituting for sea turtle shells. So you get this trend, you get this substitution of energy from nature. But now when it comes to renewables, we're supposed to believe that making energy more material intensive, is good for the environment?

Nick; But as you know, the cost, the cost and the energy intensity and the efficiency of renewables, it continues to decline. It does it just does.

Michael: No it doesn't! Actually, what you're doing, you're what you're doing is you're that's misleading. Okay, the cost of solar panels is going down. True. But that's not all there is to it, because the inherent unreliability of renewables externalizes, these additional costs onto the whole grid and so when we see renewable-heavy places, these are places that are spending a huge amount of money on all the things they have to do, So for example, just give you one example, California has to pay Arizona.

Where more and more electricity is garbage — like from renewables in California to pay Arizona to take our electricity through what’s called negative pricing — where you just are producing too much electricity when you don't need it — it's usually during sunny days when, when they're not too hot yet for air conditioners. You have too much solar and you got to go dump it on Arizona. You need to pay someone to take it. Same thing happens all over the country in terms of wind, I'm assuming there's some of that negative price in Australia.

So it's misleading to say if I say, “I bought solar panels and the electricity they produce is cheaper than the electricity a nuclear plant produces.” It’s misleading because the solar panels are not providing me electricity for most of the time. And that time they’re not, I've got to be getting my electricity from somewhere else. And if it is, indeed from solar and you're putting in batteries or something, your costs just go nuts.

Nick: Nobody I've spoken with who is looking at utility-scale power argues that you don’t need new transmission cables and new storage options or a grid that can exchange power. I mean, everyone knows this. The grid needs to change and grow and needs to evolve. Please, I don't think anyone arguing against —

Michael — that means if it becomes a renewables grid, if you, if Australia just did nuclear —

Nick: — right, and you're saying, if it were nuclear, that wouldn't need to happen, because you could build a nuclear power plant in phase one, they've already got cables there. But nuclear doesn't have a social licence to operate in Australia.

Michael: Well, but that's because of — with all due respect — I think that's due to [Points at Nick]

Nick: Yeah, that's a fair. That's an absolutely fair argument that could well be due to. Well, not just due to me but due to

Michael: I'm not pointing at you individually. I mean, you know what I mean Nick.

Nick: I know, but also due to several disasters. I mean, we can't pretend that didn't happen.

Michael: Well, no. In fact, in my book, I go into great detail on each of the disasters. And I interview the best disaster expert and, here's my short view. My view of nuclear is that it is such a radical, it's so radical, it's such a revolutionary invention, we're not going to have another one like it, you know, until the aliens give us their, you know, anti-gravity, I'm just joking, it's a major, revolutionary, revolutionary metaphysics like 10,000 years from now, it will be like that invention of nuclear.

So it was so shocking. And it completely changes national security. It means North Korea is not worried about being attacked by the United States anymore. And that's a terrifying thing. And for countries that don't have the bomb, like Australia, like Germany, like Japan, I find, I don't, I can't prove it. I find a lot of nervousness around nuclear, you would rather that it doesn't exist. You would rather that it doesn't exist, not necessarily consciously. And so when you get to these events, and there was a whole generation of baby boomers who were traumatized by Hollywood and the US government itself, the duck and cover stuff. Australia had that book "On the Beach" was the big Australia book in the '60s. Like I was, I'm, I'm born in '71. "The Day After" was I think 1983. So I was 12 when the whole family was supposed to sit down and watch this movie about nuclear war. I mean, why was I anti nuclear? That had a little bit to do with it?

Nick: Do you stand by that, by that essay on nuclear weapons? That caused some controversy a couple of years ago?

Michael: Absolutely. I stand by everything I've written. And if I don't stand by something, by the way, I've criticized it. Where my views have changed, I have tried to be a serious person. And when I change my mind, I don't mumble. I usually write about it and give a TED talk. So no, absolutely not.

It's funny, [people say ] “Michael’s saying that nuclear weapons have not made the world more dangerous. So controversial!” Well, I mean, is it? We're in a long, one of the longest periods of peace since the 17th century. And you go interview political scientists, the whole field of international relations is built on this concept of deterrence. It's like gravity or power density. It's a core concept. So this idea that there's not deterrence is this wacky idea of anti-nuclear people who think that there's some other reason that India and Pakistan, India, and China constrain their conflicts?

Nick: Yeah.

Michael: But that doesn't mean I just want to go give away... I think some people have also caricatured my position. My position has never been we're just going to go handing out these things on street corners. You know, I think that what I was trying to say there, you know, what I was trying to do a couple of things, and I do in the book too. I believe that the phobia around nuclear energy is not entirely but significantly coming from fear of nuclear weapons. It's why people go, “Oh, God! Nuclear! Ah!” Well, I mean, are they really worried about Three Mile Island or Chernobyl, which hardly killed anybody? No, they're worried, and those events themselves —

Nick: You said when you did a COP talk with James Hansen, you said that Chernobyl killed 150 people or something like that.

Michael: In the book, I rely, by the way on Geraldine Thomas, who runs the Chernobyl Tissue Bank at Imperial College London. She's a character. And so has walked me through all the information, all the data and where we're we cut where she comes out is 200 deaths total, over a lifetime after Chernobyl, and that is the World Health Organization that is based on the IAEA and

Nick: The World Health Organization figures that I will say yes, the figures are disputed between 4,000 thousand or 16,000.

Michael: Yes, and I go through that in the book. And that number is based on something called the linear no threshold. (LNT) It's based on linear, no threshold. The idea is that any amount of radiation is harmful and contributes to, you know, shorten life or disease. And it's been proven false. It's proven false by my home state of Colorado where we have much higher elevated levels of radiation, mostly due to the granite and the rock, but also due to the higher elevation, higher altitude and we have lower rates we have we have a longer life expectancy and lower and lower rates of cancer. So so it's just disproven.

And World Health Organization, you know, it has that one statement, but it also had many, many reports which I go through. I mean, they've done an absolutely terrible job of communicating to the to the public, which is why I wanted to write the book and I want people to know who Gerry was and know that her mother died of leukemia, she's not some radiation, you know, denier or something and she works at Imperial College London has never ever worked for them. History totally credible sources relied on by BBC and others you can look her up so yeah, I just think the fact that the reaction to these events is so exaggerated and I can't help it

Nick: Depending on which study you take the other thing is imagine if your right — I will not imagine that except your figures being wrong — you've also got a multi-billion dollar asset which overnight became a multi-billion dollar liability. A large chunk of land that won't be used again in anyone's lifetimes or anyone's children's or descendants lifetimes and you've got a people traumatized and hundreds of thousands of people evacuated —

Michael: — traumatized unnecessarily. I mean, like in Fukushima I talk about how —

Nick — they over there will cost so they're not there or evacuation of hundreds of thousands of people is a real cost.

Michael — No. Are you going to blame the vaccines for anti-vaxxers?

If people don't take the vaccine, because they are anti-vaxxers, they think it's gonna cause autism, is that the vaccines fault? Is that the vaccine industry's fault? Okay, so then why is it the fault of nuclear that people overreacted to the Fukushima? I mean, like the government because saying that they —

Nick: — and I'm not arguing here I'm trying to distract my head. I mean, were the evacuations unnecessary

Michael: Not all of it, but it was too long and it was too many people who could have returned much sooner.

One of the most amazing studies British Medical Journal, and they looked at people that lived in one of the most contaminated areas that had the most Fallout, the most radioactive particles in the soil. And they still had, they did internal dose measures, and they still had levels of radiation exposure far below the levels that we know to cause problems. So, and you It's all in the book. It's all there. You don't have to believe me. You should look it up because it is shocking and I don't mean to be. I mean, I told you my story about Chernobyl was just reading the World Health Organization reports and being like, even let's accept your number. Let's accept the 16,000 number.

Nick: That's my number.

Michael: Let’s say Greenpeace’s number. One hundred thousand deaths. Well, okay, but air pollution contributes to six or 7 million deaths a year

Nick: I take your point. I totally accept the cost of burning wouldn't call. I totally accept that. Yeah. And, and I think that it's been ignored for too long. I just think. Yeah, I'm glad. I'm glad we spoke. I don't know that. I will achieve more by taking more of your time. If I have follow up questions. I'll email you. If you want to speak again, I'm happy to I don't know what I write, or if I write, I hope. I'm very happy to be criticized for my work. I, you wait until arrived at before you do have another appointment.

Michael: I appreciate the experience of having those questions come at you. And feeling like I can't win. I mean, all if i if you sit there and you ask somebody outrageous questions, and then they deny it, then it just kind of you know, it just all ends up reinforcing some sense of society.

Nick: I do accept that I read the email today, and I could have done it far more graciously. My only point is this. I just presume you have been engaged in a contentious debate for a long time. So I didn't approach you as I would. Someone who is not used to dealing with the media, I was perhaps far more blunt. But I do also think that it was perfectly reasonable for me to send you a series of those questions, mainly because I was backing assertions.

Michael: I think it's fair I think I think you've inspired me to acknowledge that I may have also been a bit sensitive, and I may have also overreacted and if so I'm sorry about that. And, you know, it's just last week was the kind of crazy period and I'm super happy that you agreed to have this phone call with me. I love talking to everybody.