Pro-Human Vs. Anti-Human Environmentalism

If They Are So Alarmed By Climate Change, Why Are They So Opposed To Solving It?

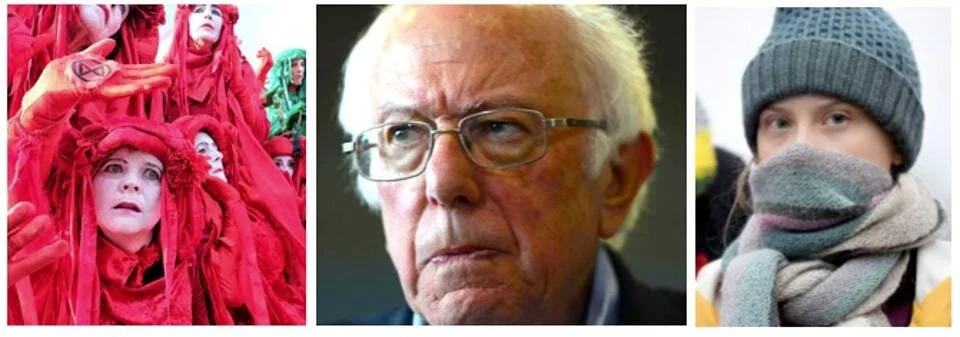

Nobody appears to be more concerned about climate change than Democratic Senator Bernie Sanders, student activist Greta Thunberg, and the thousands of Extinction Rebellion activists who shut down London last year.

Last year, Sanders called climate change “an existential threat.” Extinction Rebellion said, “Billions will die.” And Thunberg said, “I don’t want you to be hopeful” about climate change, “I want you to panic.”

But if Sanders, Thunberg, and Extinction Rebellion are so alarmed about carbon emissions, why are they fighting to halt the use of two technologies, fracking and nuclear, that are most responsible for reducing them?

Sanders says he would ban both natural gas and nuclear energy, Thunberg says she opposes nuclear energy, and Extinction Rebellion’s spokesperson said in a debate with me on BBC that she opposes natural gas.

And yet, emissions are declining thanks to the higher use of nuclear energy and natural gas. Carbon emissions have been declining in developed nations for the last decade. In Europe, emissions in 2018 were 23% below 1990 levels. In the U.S., emissions fell 15 percent from 2005 to 2016.

It’s true that industrial wind turbines and solar panels contributed to lower emissions. But their contribution was hugely outweighed by nuclear and natural gas.

Globally, nuclear energy produces nearly twice as much electricity at half the cost. And nuclear-heavy France pays little more than half as much for electricity that produces one-tenth of the carbon emissions as renewables-heavy, anti-nuclear Germany.

Natural gas reduced emissions 11 times more than solar energy and 50 percent more than wind energy in the U.S. And the unreliable nature of renewables means that they do not substitute for fossil power plants like nuclear plants do and instead must be backed up by natural gas or hydro-electric dams.

What gives? Why are the people who are most alarmist about climate change so opposed to the technologies that are solving it?

One possibility is that they truly believe nuclear and natural gas are as dangerous as climate change. This appears to be partly the case for nuclear energy, even though neither Sanders nor Thunberg offers anti-nuclear rhetoric anywhere nearly as apocalyptic as their rhetoric on climate change.

Before progressives were apocalyptic about climate change they were apocalyptic about nuclear energy. Then, after the Cold War ended, and the threat of nuclear war declined radically, they found a new vehicle for their secular apocalypse in the form of climate change.

Though nuclear energy has prevented the premature deaths of nearly two million people by reducing air pollution, and though nuclear weapons have contributed to the Long Peace since World War II, many people remain phobic of the technology.

In the case of natural gas, neither Sanders, Thunberg, or Extinction Rebellion claim it is more dangerous or worse than coal. They simply argue that we don’t need it, thanks to renewables and energy efficiency.

But Sanders learned the hard way that renewables can’t replace nuclear. Where Vermont promised to reduce emissions by 16% between 1990 and 2015, emissions instead rose 25%. Part of the reason was the closure of a nuclear plant, something Sanders advocated.

“You think we should eliminate nuclear power,” said Martha MacCallum in a Fox Town Hall meeting, “which I know they did in Vermont.”

“Sure,” said Sanders.

“But it ended up moving your emissions higher,” added MacCallum.

“Honestly, I don’t think that that’s correct,” said Sanders.

In fact, it is correct and has been confirmed by The Boston Globe, the plant’s former operator, a well-respected Vermont energy analyst, a think tank, and researchers with my organization, Environmental Progress.

As for renewables, it took Vermont nearly 10 years to build a single wind farm. At that rate, Vermont would make up for the electricity it lost from its nuclear plant 80 years from now.

It is impossible that Sanders, Thunberg, and Extinction Rebellion missed the extensive news media coverage of rising emissions, pollution deaths, and electricity prices in Germany and Japan after they closed their nuclear plants and replaced them with fossil fuels

It is impossible for Extinction Rebellion activists not to know that natural gas has been the main driver of declining emissions in Great Britain, as it has been a major news story in that country for over a decade.

And it is impossible for Thunberg not to know that her home nation of Sweden near-completely decarbonized its power sector through the use of nuclear and large dams, and that Swedish lawmakers have been debating whether or not to close nuclear reactors, which many experts believe would increase emissions.

Why Alarmism Requires Opposing Technology

What’s happening with climate change is not the first time those who are most alarmist about an environmental problem have been most opposed to solving it.

In the early 1800s, the British economist Thomas Malthus opposed birth control, even as he raised the alarm over overpopulation and the threat of famines.

After World War II, scientists and environmentalists in Europe and the U.S. opposed fossil fuels and the provision of chemical fertilizers to poor nations even as they raised the alarm about soil erosion, overpopulation, and famine.

And today, environmentalists oppose the building of hydro-electric dams and flood control in poor nations, even as they raise the alarm about climate-driven flooding.

In every case, alarmists claim some moral basis for their opposition to technical fixes. Malthus argued that birth control was against God’s will. Malthusian scientists after World War II asserted that fertilizers, tractors, and fossil fuels worsened people’s lives. And opponents of hydro-electric dams and flood control claim those technologies were an “inappropriate” and expensive Western imposition.

And in every case, they claim their solutions are morally superior. Malthus argued for delaying marriage. Malthusians argued for small-scale renewables and labor-intensive farming. And opponents of dams and flood control argue for “ecosystem services” like wetlands and barrier islands.

But hydro-electric dams are one of the cheapest ways that poor nationscan gain access to reliable electricity, and the people who live around them tend to be grateful to get them.

Developing nations avoid flooding through the same dams, levees, embankments, culverts, gutters, dikes, levies, basins, storm drains, pump stations, and seawalls that rich nations have used to protect their citizens for hundreds of years.

While UN officials and rich-world journalists are smitten with the notion of poor countries “leapfrogging” from wood and dung to solar panels, such electricity is far too unreliable, even with batteries, and expensive, to power farms, factories, and cities.

Economic development requires as much energy today as it did 50 years ago, despite, and to some extent, because of, higher energy efficiency. There is no rich, low-energy nation and no poor, high-energy one.

The End of Civilization

Apocalyptic environmentalists like Sanders, Thunberg, and Extinction Rebellion insist that if we don’t enact their agenda, industrial civilization will come to an end. But if they are so concerned with protecting industrial civilization, why do they advocate solutions that would end it?

The industrial revolution in England was only made possible through intensified agriculture and the use of coal for manufacturing, which delivered far more energy for far less labor. While the energy density of a lump of coal is twice that of a lump of wood, the “power density” of a coal mine is 25,000 times larger than that of forests, calculatesenergy analyst Vaclav Smil.

Today’s power-dense cities require power-dense fuels. Today’s cities take up just 0.5 percent of the Earth’s ice-free land surface. In the U.S., the energy system requires just 0.5 percent of national land. By contrast, achieving 100% renewables would require 25 to 50 percent of all land in the US, notes Smil.

The flip side of renewables’ low energy density is their low return on energy invested. Where nuclear and hydroelectric dams return about 75 and 35 times more, respectively, in energy than they require, solar and wind can end up returning just 1.6 and 4 times more. Today our high-energy civilization relies on fuels that on average deliver a return 30 times higher than the energy-invested.

While Sanders puts a high-tech gloss on his web page promoting a “Green New Deal,” the creators of the low-energy, renewables-only vision were unabashed in their desire to transform today’s high-energy industrial society to a low-energy agricultural one.

Do Sanders, Thunberg, Extinction Rebellion and other apocalyptic greens really believe that, by raising the alarm about the end of the world, they will persuade societies to choose the low-energy path?

Perhaps. But they may also fear, consciously or unconsciously, that the outsized role played by natural gas and nuclear means that climate apocalypse can be averted without any of the radical societal transformations they demand. After all, if nations were to simply use natural gas to transition to nuclear, there would be little need to stop traffic in London, moralize about the virtues of foregoing meat, flying, and driving, or deploy renewables.

Anti-Nuclear Bias Of UN & IPCC Is Rooted In Cold War Fears Of Atomic And Population Bombs

Advocates of nuclear power were surprised yesterday when a new report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) attacked the clean energy source as dirty and dangerous.

They shouldn’t have been. In truth, the IPCC has been heavily biased against nuclear and toward renewables throughout its 20-year existence.

Consider:

In 2015, IPCC published a “Special Report on Renewables” that excluded nuclear, and has never published a special report on nuclear, even though it requires just 6% of the material inputsof solar and is more renewable than either solar or wind;

In report after report, IPCC attacks “nuclear waste” (used fuel) as a major problem — in truth, its radiation never hurts anyone — but never mentions wind or solar panel waste, which remains toxic forever;

IPCC falsely alleges that nuclear “cannot compete against natural gas,” a fossil fuel contributing to climate change, while promoting solar and wind, which make electricity expensive;

IPCC describes nuclear as a “mature energy technology” even though it is far younger than every other major source of energy including solar, wind turbines, hydro-electric dams, and fossil fuels;

Now, IPCC’s new report ignores research published in Science by climate scientist James Hansen showing the deployment of nuclear has been 12 times faster than solar and wind and instead cites a study by anti-nuclear author Amory Lovins attacking Hansen and purporting to debunk his study in a journal with an impact factor one-tenth as large as Science’s.

What gives? Why is an organization supposedly dedicated to solving climate change so opposed to the only scalable source of clean energyproven capable of rapidly replacing fossil fuels?

To answer these questions, we have to go back in time — back to the rise of nuclear fear.

Oppenheimer’s Revenge

In 1892, a rumor spread that Thomas Edison was making a new device that could destroy a whole city. This rumor, in turn, inspired a satiric newspaper account of a mad scientist blowing up England with a “doomsday machine.”

In his 1913 science fiction novel, A World Set Free, H.G. Wells describes “atomic bombs ... that would continue to explode indefinitely” and create fall-out in the form of “radio-active vapor.”

And yet by World War II, some scientists believed, paradoxically, that atomic weapons could end world war. When Danish physicist Niels Bohr visited the father of the atomic bomb, J. Robert Oppenheimer at Los Alamos, in 1943, his first question was, “Is it really big enough?”

According to Oppenheimer’s biographers, Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin in their Pulitzer-winning American Prometheus, Bohr was asking, “would the new weapon be so powerful as to make future wars inconceivable?”

Bohr — heavily influenced by the existentialist Christian philosopher Soren Kierkegaard’s paradoxical view that profound faith requires equally profound doubt — sent a memo to President Franklin Roosevelt. Richard Rhodes summarizes it in his masterpiece, The Making of the Atomic Bomb.

The weapon devised as an instrument of major war would end major war. It was hardly a weapon at all, the memorandum Bohr was writing in sweltering Washington emphasized; it was “a far deeper interference with the natural course of events than anything ever before attempted” and it would “completely change all future conditions of warfare.” When nuclear weapons spread to other countries, as they certainly would, no one would be able any longer to win.

The night of the Hiroshima bombing, Oppenheimer echoed Bohr when he told his men that “the atomic bomb is so terrible a weapon that war is now impossible.” After the bombing of Nagasaki, physicist Ernest Lawrence told Oppenheimer that the bomb was so horrible it wouldn’t ever again be used.

After the war, Oppenheimer argued that atomic scientists working under the auspices of the United Nations should control the entire nuclear fuel cycle — including mines and nuclear plants in foreign nations — a proposal that was rejected immediately by the U.S., Britain, and the Soviet Union.

Soon, scientists went from worrying whether the fission bomb was big enough to fearing that fusion (thermonuclear) bombs were too big, note Oppenheimer’s biographers. Oppenheimer urged the Pentagon to build smaller, more tactical nuclear weapons, on the grounds that they would be more useful, while he simultaneously pressed for disarmament. But, write Bird and Sherwin, “by 1949, [Oppenheimer] despaired of making progress in the foreseeable future on nuclear disarmament.”

The problem was he could never explain how disarmament would work. “You know, I listened as carefully as I knew how,” said Oppenheimer ally and Secretary of State, Dean Acheson, “but I don’t understand what ‘Oppie’ was trying to say. How can you persuade a paranoid adversary to disarm ‘by example’?”

In response to his frustrations, write Bird and Sherwin, “Oppenheimer tried to use his influence to put a damper on the government’s and the public’s growing expectations for all things nuclear” — including atomic energy, something Oppenheimer just three years earlier had said was critical for the “continuation of this industrial age.”

In the summer of 1949, write Bird and Sherwin, “the press quoted [Oppenheimer] as saying that ‘nuclear power for planes and battleships is so much hogwash… he also talked about the potential dangers inherent in civilian nuclear power plants.’”

The war on nuclear had begun.

Of Babies and Bombs

By 1957, a veteran of the Manhattan Project, Ralph Lapp, told CBS’s Mike Wallace that fall-out from weapons testing would result in “leukemia,” a false claim based on bad science.

“Suppose,” asked Wallace, invoking the doomsday machine, “science could invent a source of fantastic energy that would be a great good to mankind but that also might enable a scientist to destroy the entire world with the push of a button — as a scientist would you help invent that force?”

Lapp replied, “I would not. I think this is the case where we are finding that scientists are coming more... are becoming more and more socially conscious.”

Nuclear weapons went from being a guarantor of peace through deterrence for physicists Bohr, Lawrence, and the pre-1949 Oppenheimer to being a cartoon doomsday machine in the hands of crusading scientists and sensationalizing journalists.

Women and mothers were targeted. “Radioactivity is poisoning your children,” read the headline in a January 1957 issue of McCall’s, a leading women’s magazine.

Even the journal Science, in 1961, published an article noting that strontium-90, a radioactive isotope produced by weapons testing, being found in the teeth of children born during nuclear weapons testing, even though the levels were 200 times less than those found to cause cancer.

Just 0.2% of our exposure to ionizing radiation comes from fall-out.

In truth, just 0.2% of our exposure to ionizing radiation comes from fall-out, and 0.1% from nuclear plants, while 15% comes from medical devices. A full 84% of our exposure is from the natural environment.

One year later, an enterprising Sierra Club activist preyed upon fears of fall-out to kill a nuclear plant in northern California. His allies came to fear that infinite nuclear energy would result in overpopulation.

“It’d be little short of disastrous for us to discover a source of clean, cheap, abundant energy,” wrote anti-nuclear leader Amory Lovins, “because of what we would do with it.”

Neo-Malthusian conservationists often hid their motivations. When asked in the mid-1990s if he had been worried about nuclear accidents, Sierra Club anti-nuclear activist Martin Litton replied, “No, I really didn’t care because there are too many people anyway … I think that playing dirty if you have a noble end is fine.”

The reason the neo-Malthusians had to attack nuclear power is because it undermined their case that the world was on the brink of resource scarcity and environmental degradation from overpopulation. Infinite nuclear energy meant infinite fertilizer, freshwater, and food — and a radically reduced environmental footprint.

And so they grabbed on to the fall-out scare pioneered by Lapp. “[A] million people die in the Northern Hemisphere now, because of plutonium from atmospheric [weapons] testing,” claimed Sierra Club's Executive Director.

Others invented problems. In 1971, the physicist John Holdren made the pseudoscientific claim that “the second law of thermodynamics and heat transfer theory put an upper limit on society’s use of energy.”

Notes historian Thomas Wellock, “Holdren’s thermodynamic arguments did not single out nuclear power as the chief problem,” but “they reduced nuclear power to just another problematic energy source.”

Two years later, Holdren became an advocate of nuclear disarmament, low-energy living, and renewables. His 1977 textbook, Ecoscience: Population, Resources, Environment, proposed international control of “the development, administration, conservation and distribution of all natural resources.”

U.N. Promotion of Scarcity

The United Nations embraced the neo-Malthusian attack on nuclear power in a 1987 report called “Our Common Future.” All but one of the report’s 194 references to nuclear are negative. “The potential for the spread of nuclear weapons is one of the most serious threats to world peace,” reads a typical passage.

Rather than move to fossil fuels and nuclear, as rich nations had done, poor nations should instead use wood fuel more sustainably, recommends the report. “The wood-poor nations must organize their agricultural sectors to produce large amounts of wood and other plant fuels.”

The lead author of “Our Common Future” was Gro Brundtland, former Prime Minister of Norway, a nation which just a decade earlier had become fabulously wealthy thanks to its abundant oil and gas reserves.

Figures like Brundtland promoted the idea that poor nations didn’t need to consume much energy, which turned out to be howlingly wrong. Energy consumption is as tightly coupled to per capita GDP today as it was when today’s rich nations were themselves poor.

Even so, the IPCC report on keeping temperatures below 1.5 degrees rests heavily on the idea that poor nations can grow rich while using radically less energy. “Pathways compatible with 1.5°C that feature low energy demand,” IPCC says, “show the most pronounced synergies and the lowest number of trade-offs.”

While most poor nations have understandably rejected IPCC’s advice to stay poor, rich nations followed IPCC’s advice and poured about $2 trillion into solar and wind.

Share of global energy coming from clean energy sources

EP

The result? The share of energy globally coming from zero-emission energy sources has grown less than 1% since 1995. The reason? The increase in energy from solar and wind has barely made up for the IPCC-encouraged decline in nuclear.

That reality didn’t seem to bother Holdren, who served as President Barack Obama’s science advisor from 2009 to 2017. While in power, Holdren promoted solar and wind and cast aspersions on nuclear — in language very similar to that used by the IPCC.

After the Apocalypse

The good news is that the Cold War fears of nuclear and population bombs, hyped by misanthropic Malthusians, turned out to be unfounded. As nations grew rich, their fertility rates plunged. And as nuclear weapons spread, the number of deaths from wars and conflicts declined 95%.

As for mad men with doomsday machines, sometimes they fall in love. President Donald Trump credits North Korean President Kim Jong-Un’s “beautiful letters,” but it was more likely his nuclear-armed ICBMs, which may also be the key to Korea’s eventual reunification.

The bomb exercises restraint. When General William Westmoreland tried to move nuclear weapons to South Vietnam, he was immediately over-ruled by President Lyndon Johnson — a man who didn’t hesitate to order the bombings of civilian populations with conventional weapons.

The paradoxical nature of the new situation — where “the only winning move is not to play,” in the memorable line from the 1983 movie, “War Games” — takes getting used to. Historian Richard Rhodes quotesSoviet Leader Nikita Khrushchev’s reflections upon his “initial encounter with existential deterrence” in 1953:

When I was appointed First Secretary of the Central Committee and learned all the facts about nuclear power, I couldn’t sleep for several days. Then I became convinced that we could never possibly use these weapons, and when I realized that, I was able to sleep again.

As for doomsday, it appears to be behind us. Of the 50 million people who died in World War II, 99.5% were killed by conventional, not nuclear, weapons. What emerged on the other side of the apocalypse was a bomb big enough to end world war.

As such, Niels Bohr, the early Oppenheimer, and Ernest Lawrence may have been right all along. Concludes Rhodes, the bomb’s wisest and most humanistic biographer:

The discovery in 1938 of how to release nuclear energy introduced a singularity into the human world — a deep new reality, a region where the old rules of war no longer applied. The region of nuclear singularity enlarged across the decades, sweeping war away at its shock front until today it excludes all but civil wars and limited conventional wars …

Science has revealed at least world war to be historical, not universal, a manifestation of destructive technologies of limited scale. In the long history of human slaughter, that is no small achievement.