Bottom Line:

Major strides in aquaculture allow us to harvest more fish to meet growing demand while using less of the stocks in the ocean. This insures. wild populations can recover and protects the world’s valuable marine ecosystems.

FAQ

What is overfishing?

Overfishing is when more sea life, usually fish, is taken for consumption than the population can replenish, leading to declining numbers of that species.

If the population of a species in a particular place, referred to as a “fish stock”, gets too low, it can collapse and disappear. This has significant impacts on the ecosystem the population belonged to, as well as on the food supply and economic prosperity of the towns that relied on harvesting the fish.

What is bycatch?

The reality of fishing is that the process involves unintentionally catching sealife that isn’t suitable for use, which the industry labels as “bycatch”. It is most commonly used to describe animals caught by fishing equipment other than the species targeted.

One of the most famous examples of bycatch are the dolphins that die in tuna nets. Dolphins and tuna in the Pacific Ocean are often found swimming together, which led to fishing practices that involved catching tuna and dolphins together in a net, then releasing the dolphins. The problem is that the dolphins would drown in the tuna nets, so those that were released were often dead, dying, or severely injured. Significant reductions in dolphin populations led to public backlash which ended up inspiring the US Marine Mammal Protection Act.

It is estimated that over 40 percent of the global marine catch is bycatch. This includes endangered animals of high conservation value including sea turtles, seals, and sea birds.

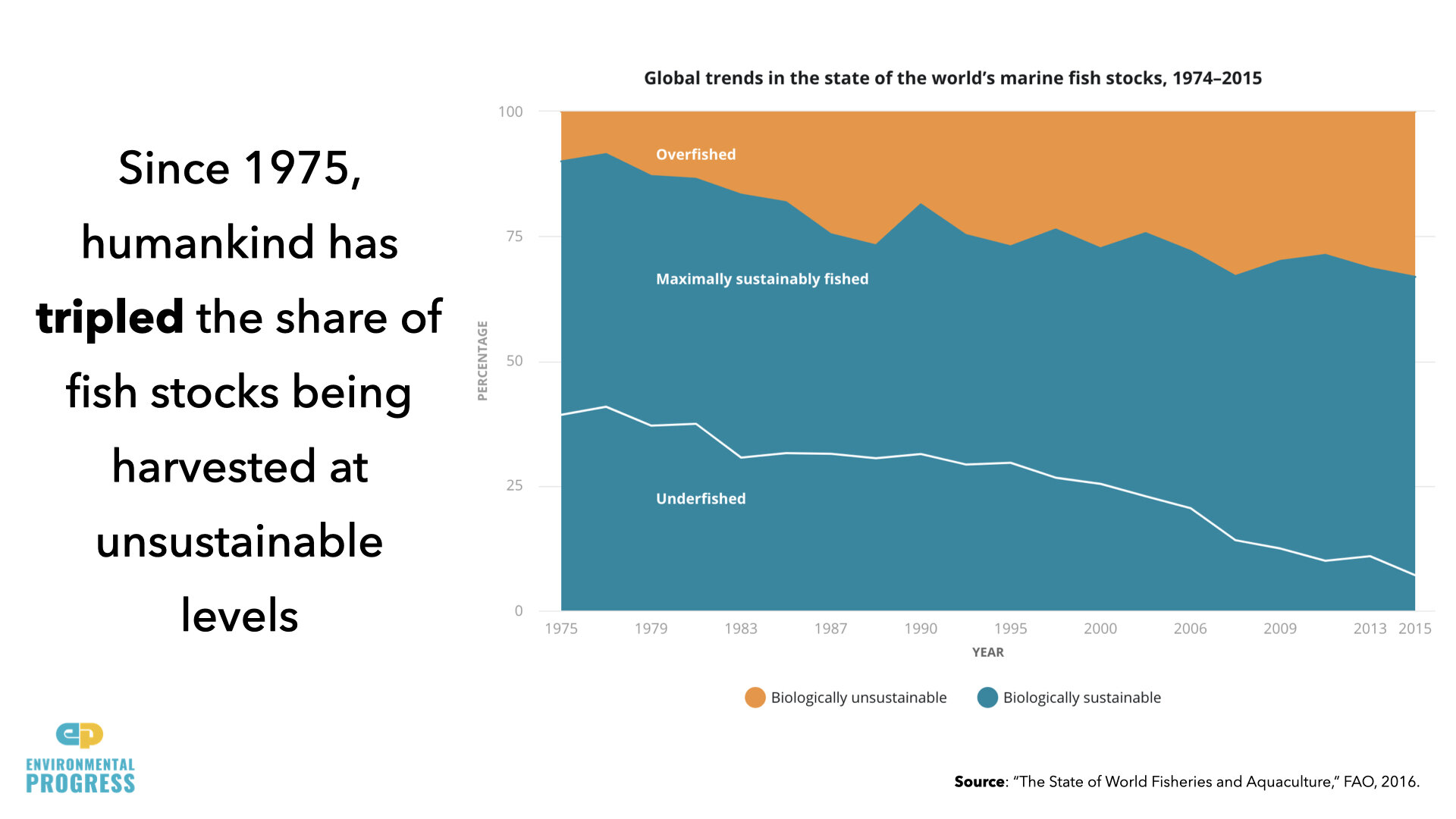

How big of a problem is overfishing?

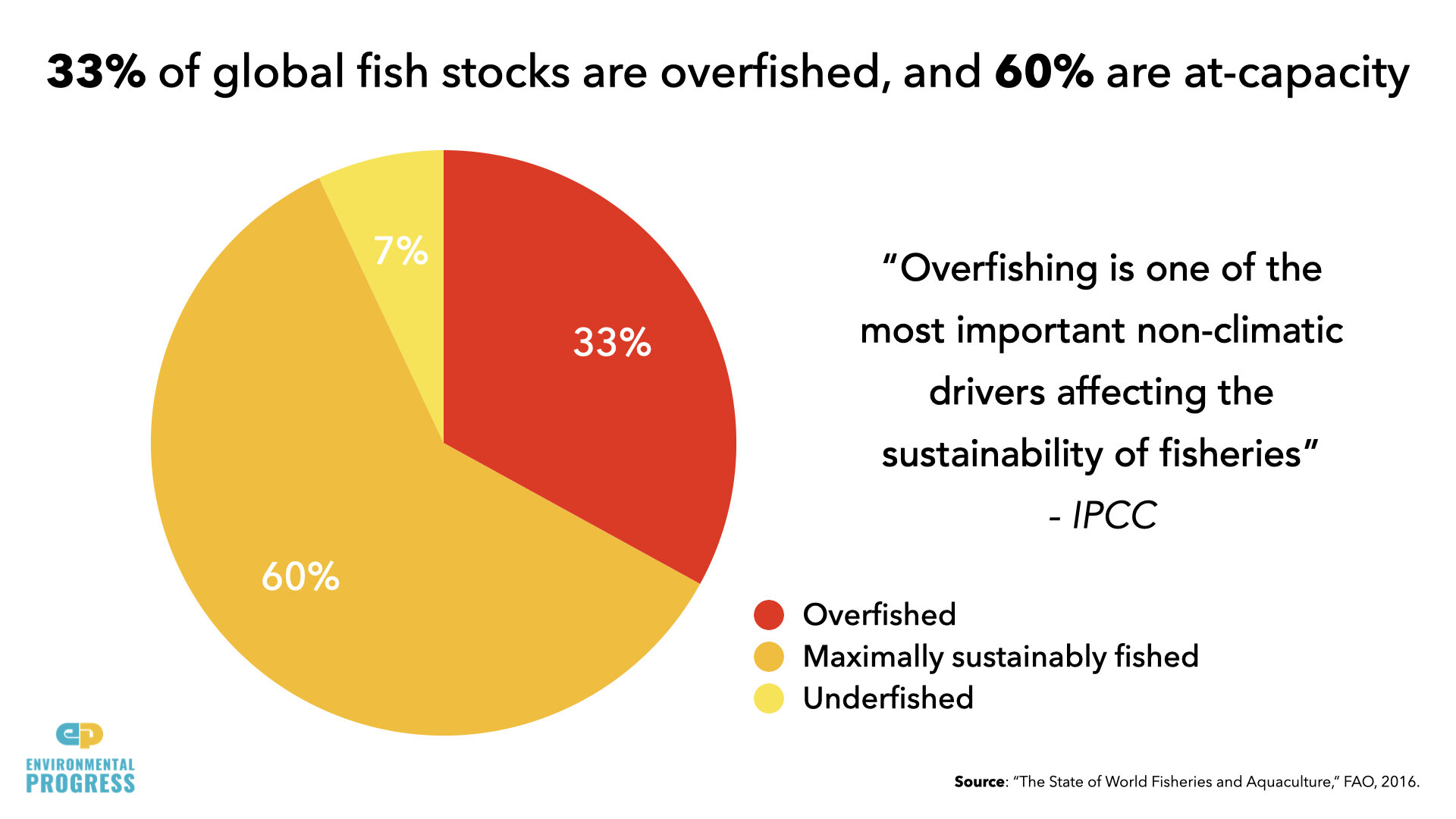

According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, overfishing “is one of the most important non-climatic drivers affecting the sustainability of fisheries.”

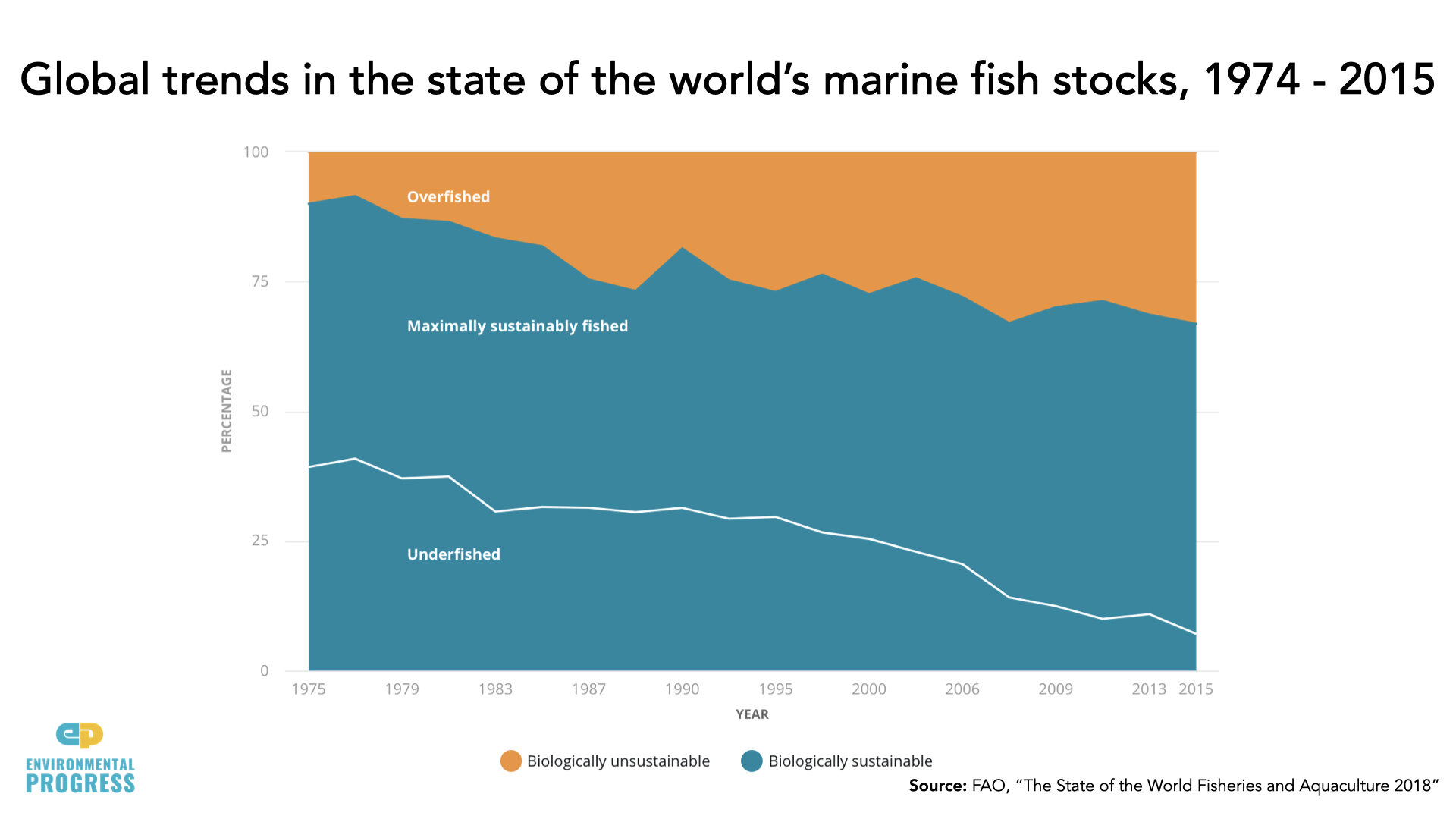

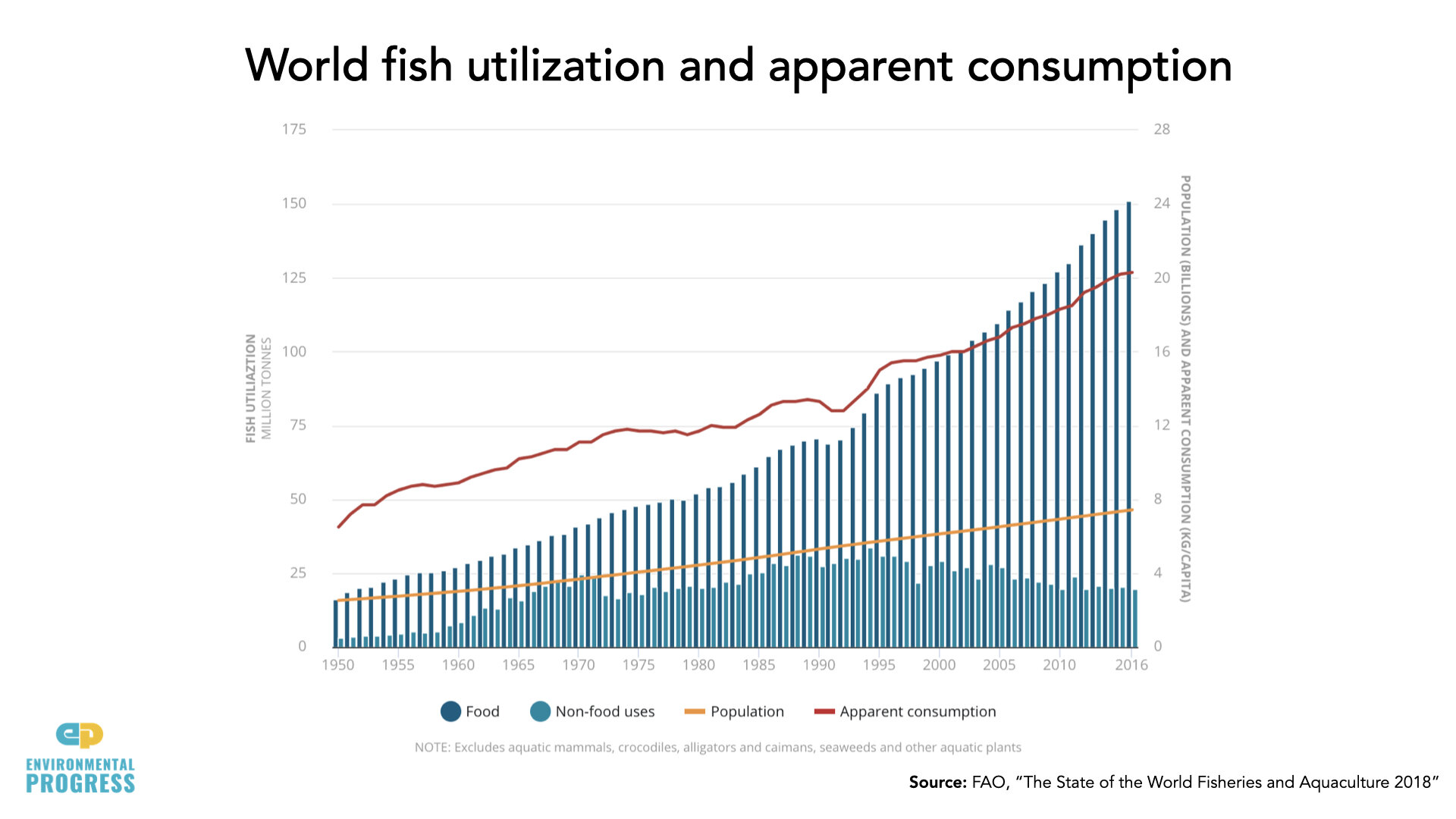

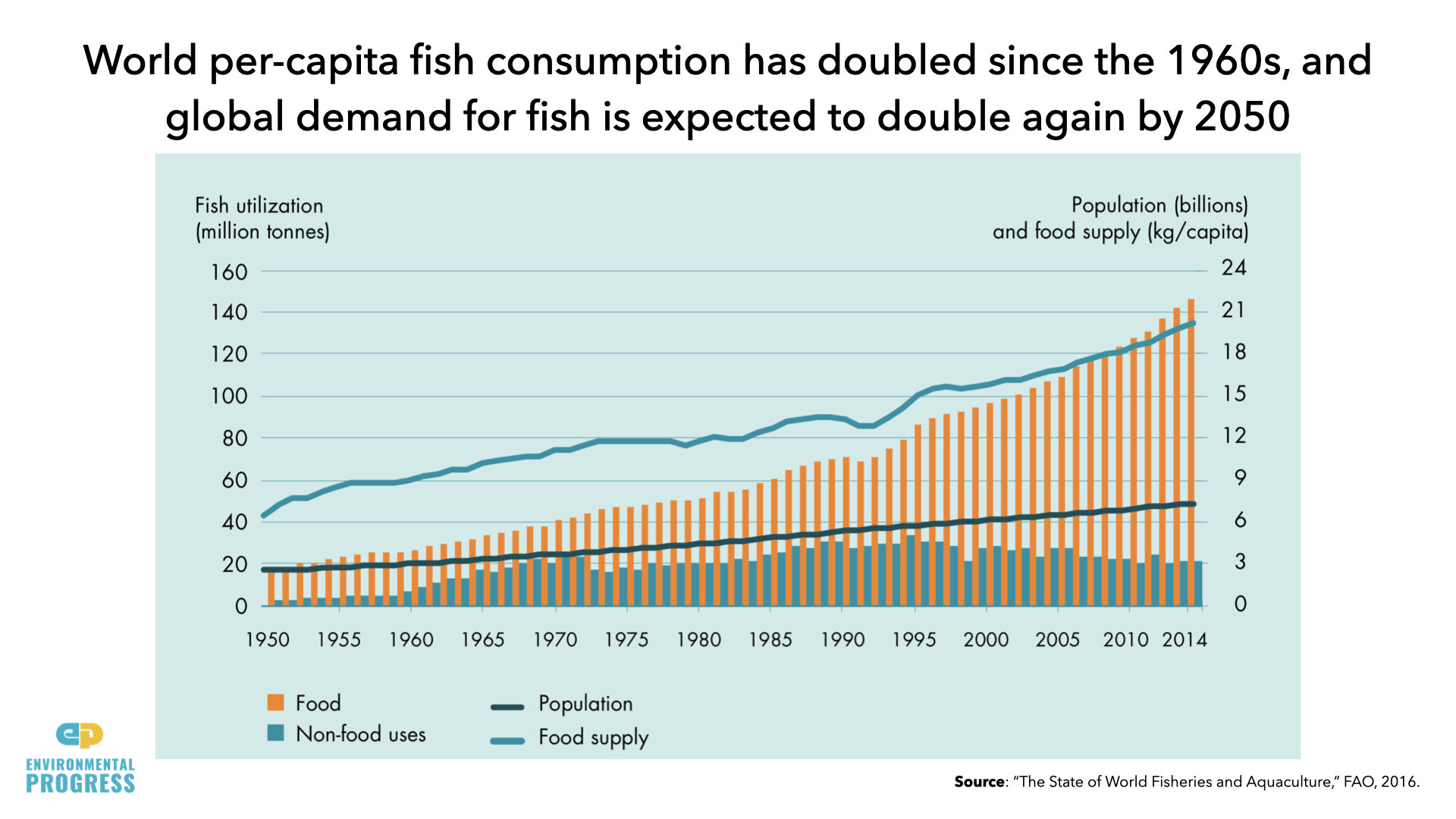

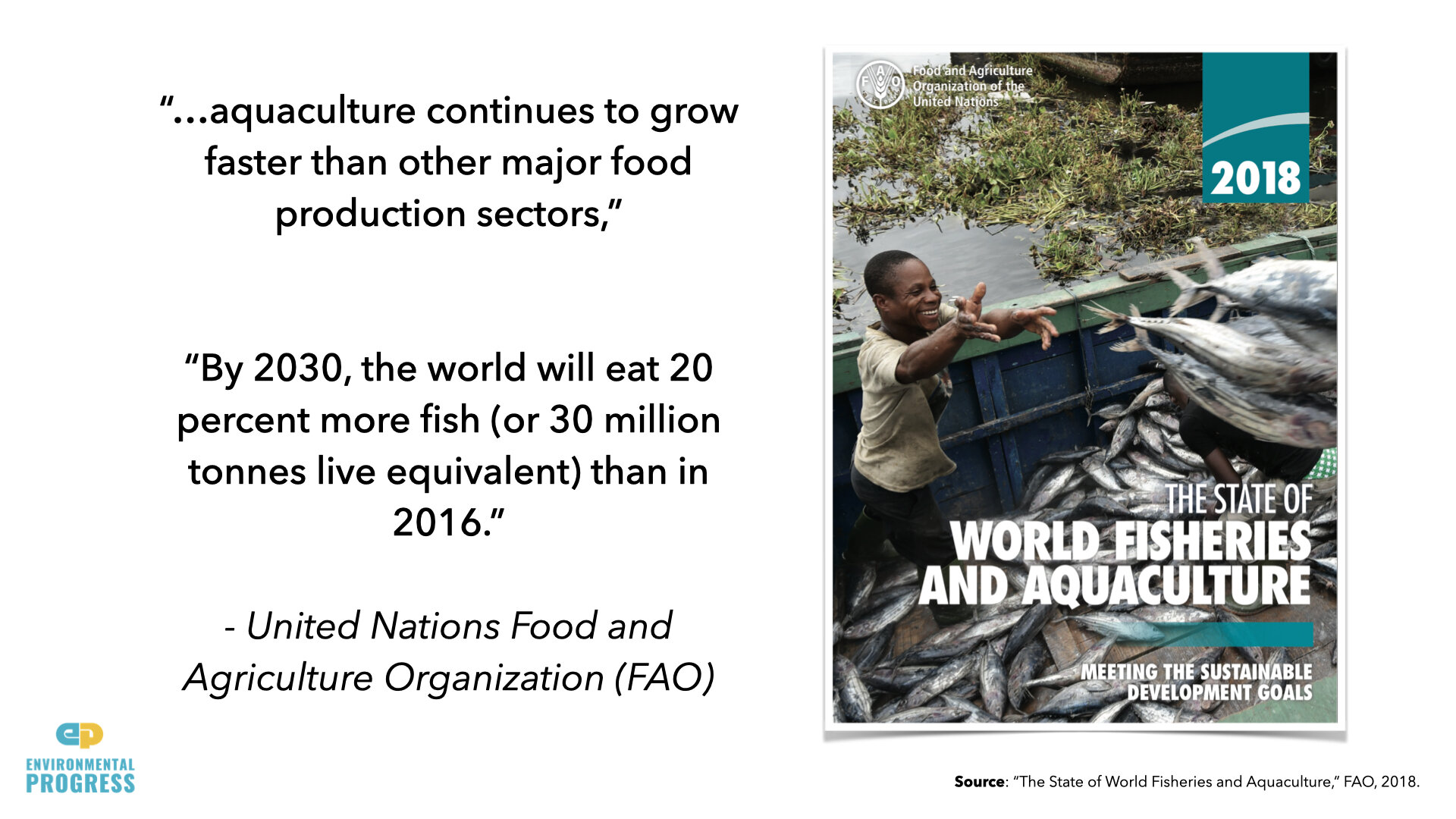

Today, 90% of the world’s fish stocks are either overfished or at capacity, meaning they are close to or just barely above the maximum they can be harvested before seeing their populations collapse entirely. Further, global demand for fish has increased significantly over the past 50 years and due to rising wealth and a growing population, is projected to double by 2050.

Changes to wildlife populations can have effects up and down the local food chains that can disrupt entire ecosystems, as was observed after dramatic declines of shark populations in the North Atlantic. Overfishing has resulted in many local extinctions, making it an incredibly serious conservation problem.

Why don’t we just stop eating seafood?

Seafood is an important source of food and nutrition for much of the world. In 2015, fish accounted for 17 percent of the global population’s intake of animal protein. Seafood is especially important in some developing countries and island nations, where it provides more than 20 percent of a person’s average protein intake. Fish is also critical for rural populations, which often have less diverse diets and higher rates of food insecurity.

What measures are being used to curb overfishing?

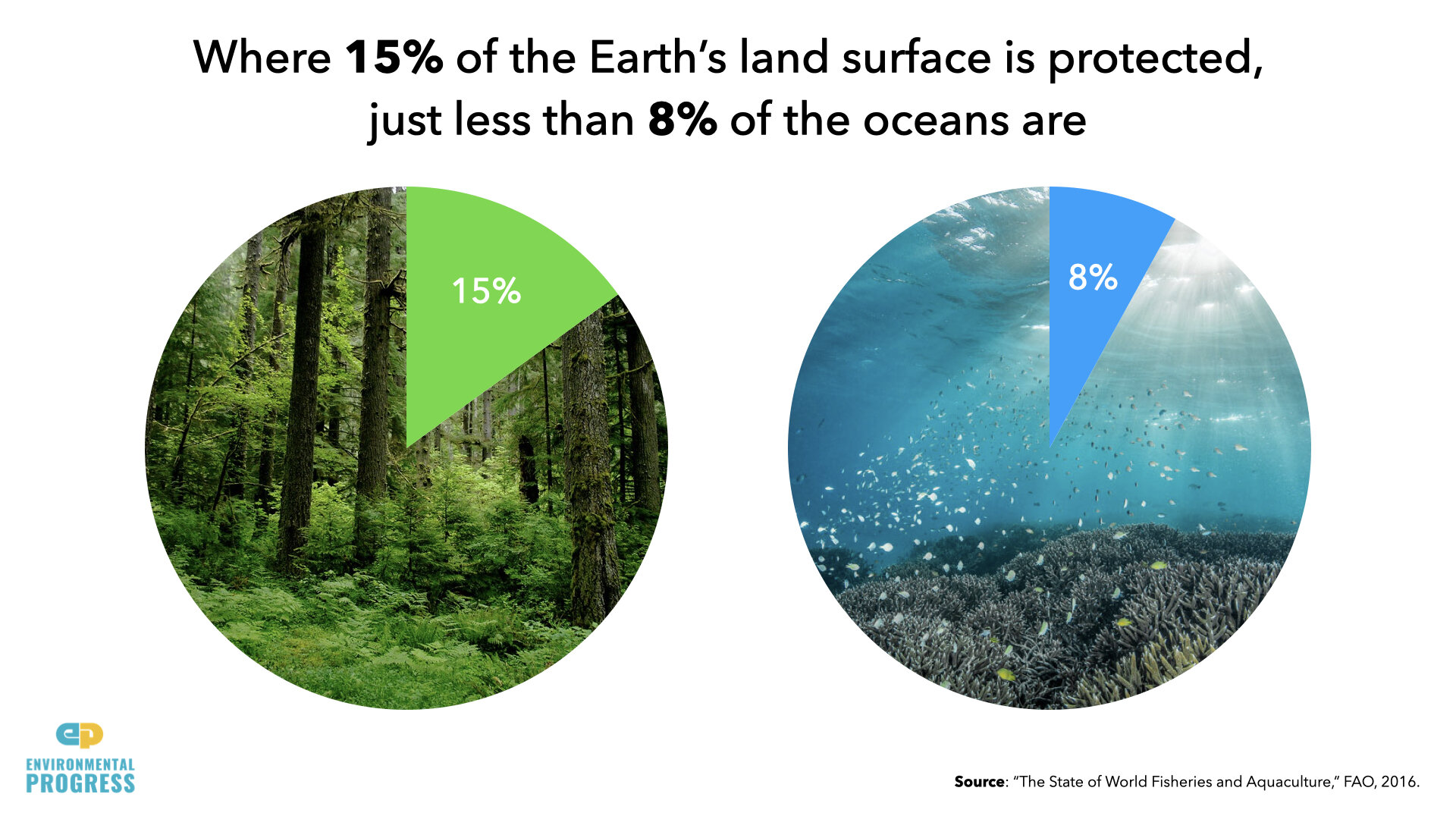

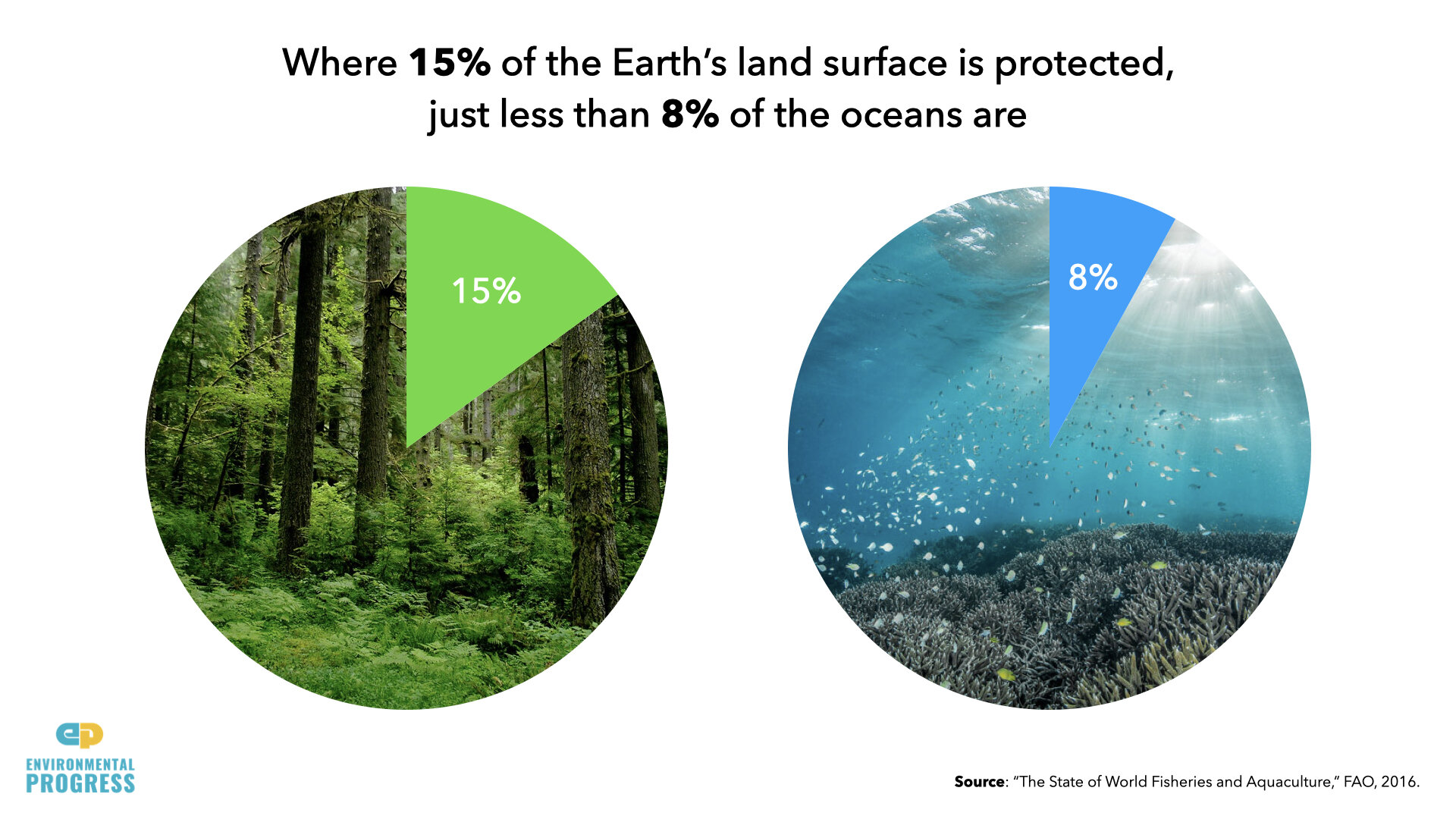

Around the world, governments, intergovernmental organizations, and non-profits are working to control overfishing. One way this problem is being tackled is through regulatory measures imposed on fisheries to ensure they are harvesting at sustainable levels. Bag limits, quotas, size limits, the implementation of licensing or seasons, and the creation of reserved or protected areas are all measures that have been used to control the amount of fish taken from local populations.

Fisheries are also working to reduce bycatch by using better techniques and equipment. Specialized traps and nets allow fisheries to reduce the amount of non-target marine life they capture.

Consumers are also playing their part in protecting marine ecosystems from overfishing. As people have become aware of the seriousness of overfishing, consumers with choice are increasingly committing to buying sustainable seafood, which means fish were farmed or fished in a way that would not harm the ecosystem from which it came.

How are we going to meet growing demand without overfishing?

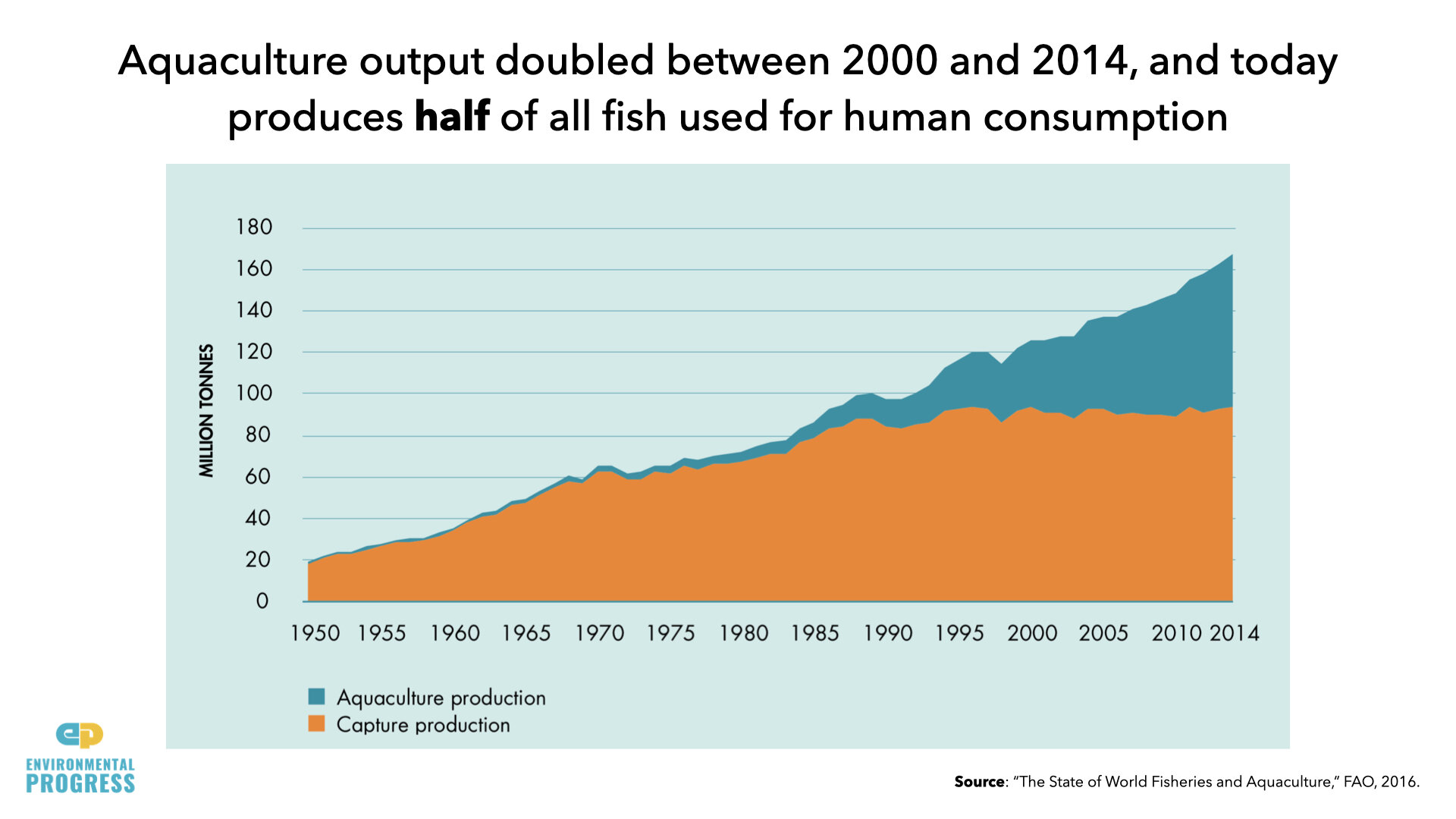

Aquaculture, or fish farming, could be used to dramatically increase the supply of seafood and simultaneously reduce the environmental harm of fishing.

Farming led to humans producing more food on less land, allowing us to use less nature while also providing enough food to meet the needs of a growing population. Aquaculture is a very similar concept: rather than harvesting wild fish from marine ecosystems, populations are bred and grown in controlled conditions and harvested at a sustainable rate.

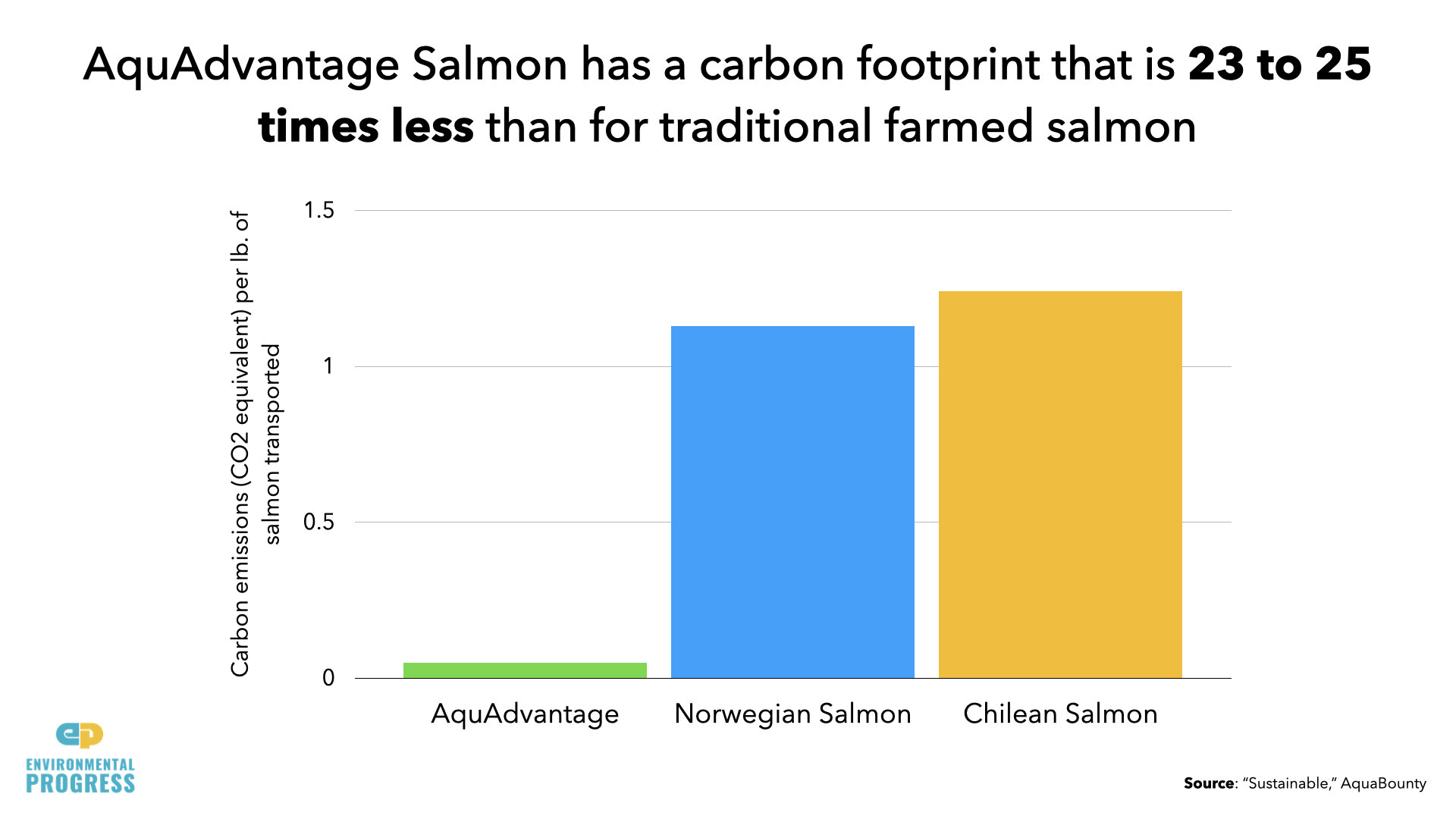

A big environmental benefit from aquaculture comes from moving fish farms from oceans to land, which reduces the impact on marine environments and allows for closed or near-closed systems where water is constantly being cleaned and recycled. Plus, raising seafood in local hatcheries will result in fewer carbon emissions, as the fish doesn’t need to be shipped and flown around the world.

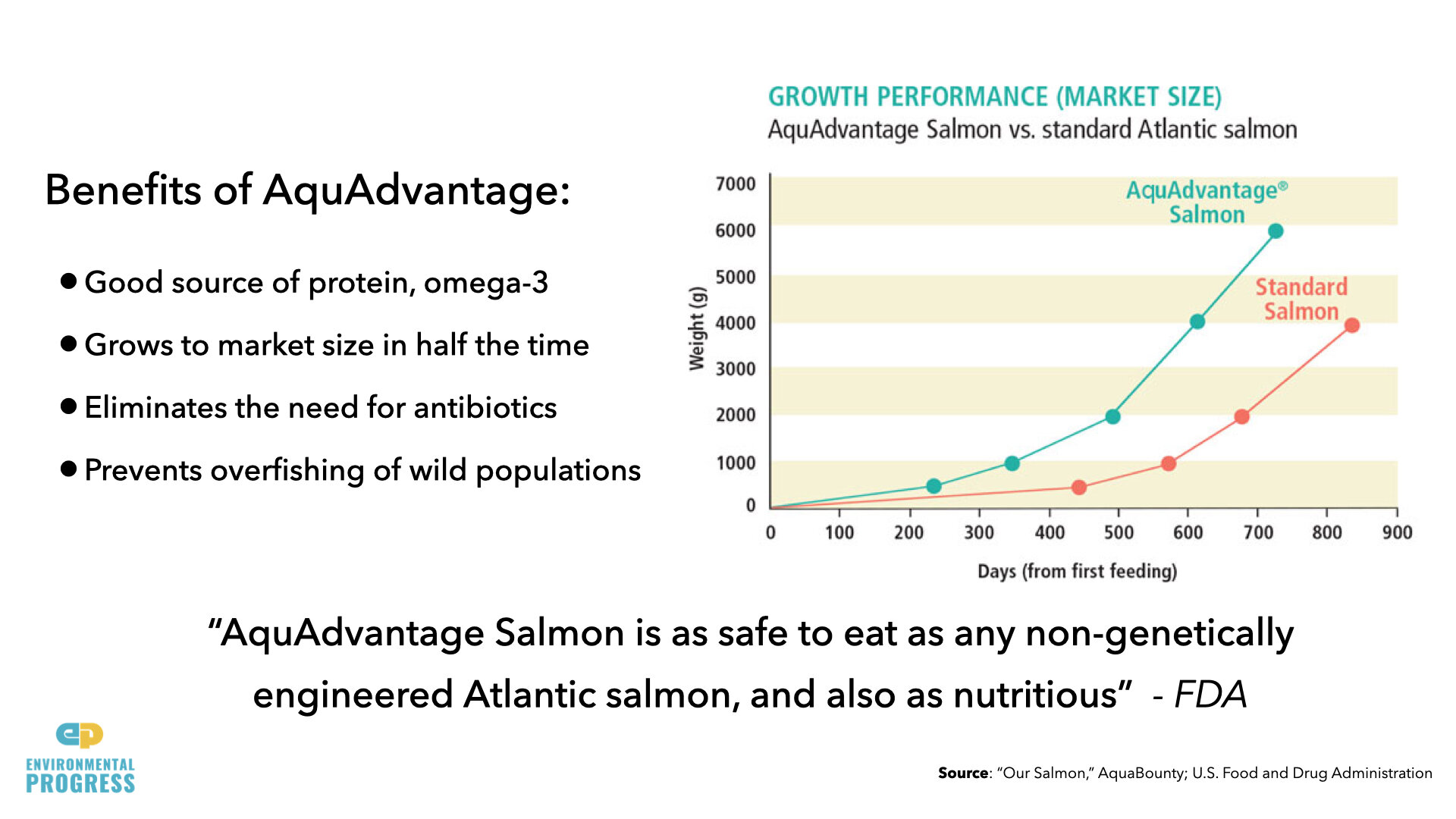

Another innovation in fish farming has been the development of genetically-modified fish. AquAdvantage salmon, developed by AquaBounty Technologies in 1989, grows twice as fast and needs 20 percent less feed than Atlantic salmon. While eight pounds of feed is needed to harvest one pound of beef, only one pound of feed is required for one pound of AquAdvantage salmon.

Are there concerns about farmed fish?

Fish farming is not without its problems. For example, some of the first fish farms (which were actually shrimp farms) were created by clearing mangrove forests and resulted in the pollution of waterways by chemicals and nutrients.

Many environmental groups rightfully concerned about these issues spoke out against aquaculture early on.

Fortunately over time, the negative environmental impacts of aquaculture have significantly declined. More care is being taken in siting these farms, and better yet, more farms are being moved to on-land facilities.

Now, early critics of aquaculture are some of its loudest advocates. William Muir, the scientist who first raised the concern that genetically engineered fish could threaten wild fish stocks, said “I won’t argue that a genetically engineered salmon will never find its way into the ocean. But there’s nothing in this fish that would last more than a single generation because of its low fitness.”

Overfishing Slides