Bottom Line:

Human-caused climate change is an environmental issue we will need to address over the course of this century. However, how much risk countries face from climate change is determined by wealth and standard of living rather than exactly how much the climate changes. Many people living in poor countries are vulnerable to extreme weather today.

Because wealthier nations are more resilient and more capable of adaptation, our goal should be to reduce emissions over the next century and keep temperatures as low as possible without undermining economic development.

FAQ

What is climate change?

Climate change refers to the ongoing rise in global temperatures we’re witnessing as a result of record amounts of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, as well as the effects associated with warming. Climate change is largely a result of human activity including burning fossil fuels, deforestation, and agriculture.

How long do we have to act?

We should think of climate change not as a ten-year problem, but a ten-decade problem.

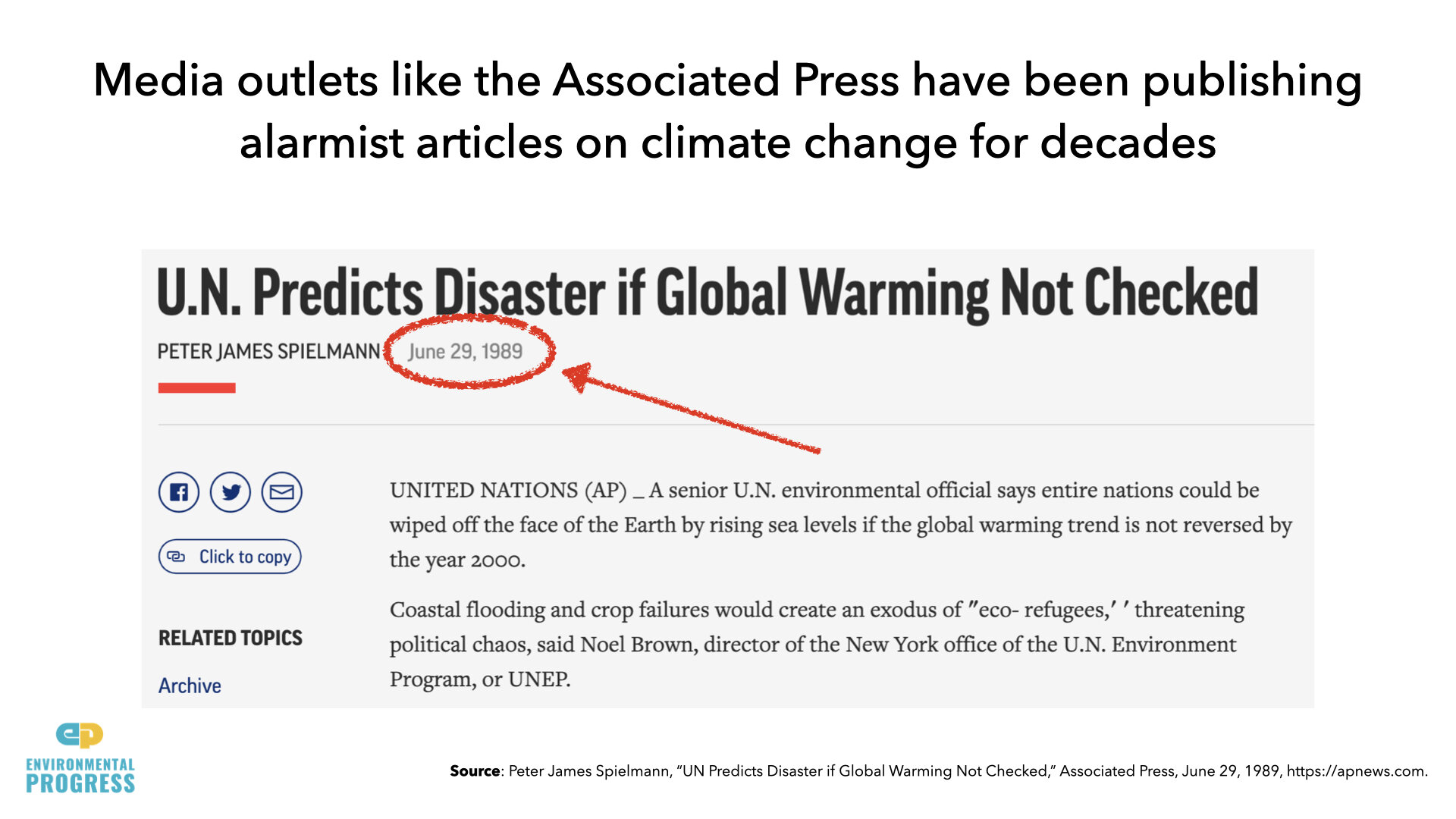

Claims that we have 12 years to deal with climate change before we reach irreversible harm and others like it aren’t supported by the scientific community.

Gavin A. Schmidt, a climatologist, climate modeler and Director of the NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies, said, “Nothing special happens when the ‘carbon budget’ runs out or we pass whatever temperature target you care about, instead the costs of emissions steadily rise.”

Andrea Dutton, a paleoclimate researcher at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, explained, “For some reason the media latched onto the twelve years (2030), presumably because they thought that it helped to get across the message of how quickly we are approaching this and hence how urgently we need action. Unfortunately, this has led to a complete mischaracterization of what the [IPCC report on climate change] said.”

What about natural disasters?

The United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) concluded that climate change so far has not resulted in increases in the frequency or intensity of many types of extreme weather, including tornadoes, floods, hurricanes, or droughts.

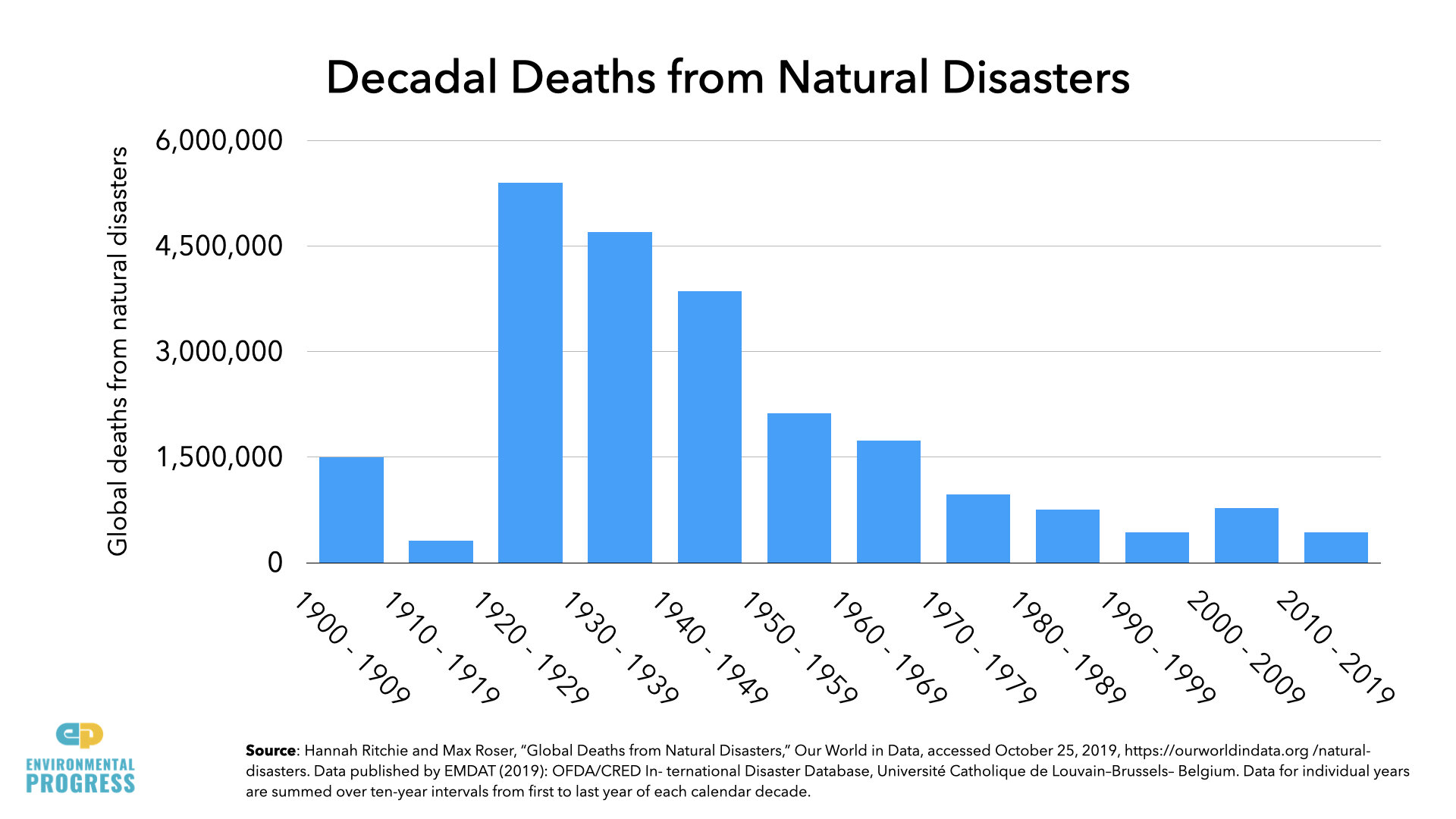

The number of deaths each decade resulting from natural disasters actually declined by 92% since the peak in the 1920s. While the cost of natural disasters has risen over that period of time, it is because there are more people and property in harm’s way than in the past, not because disasters are worsening.

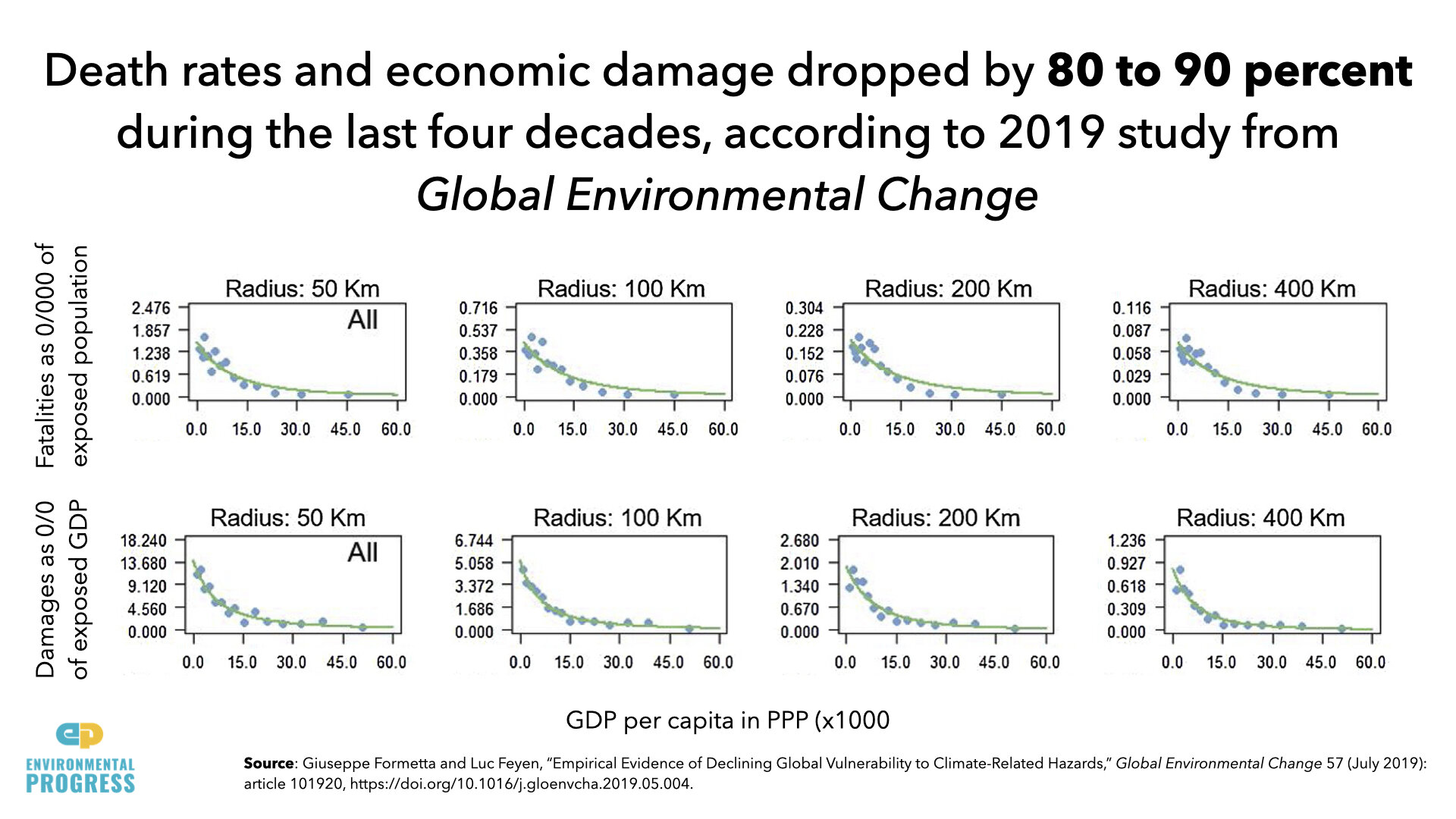

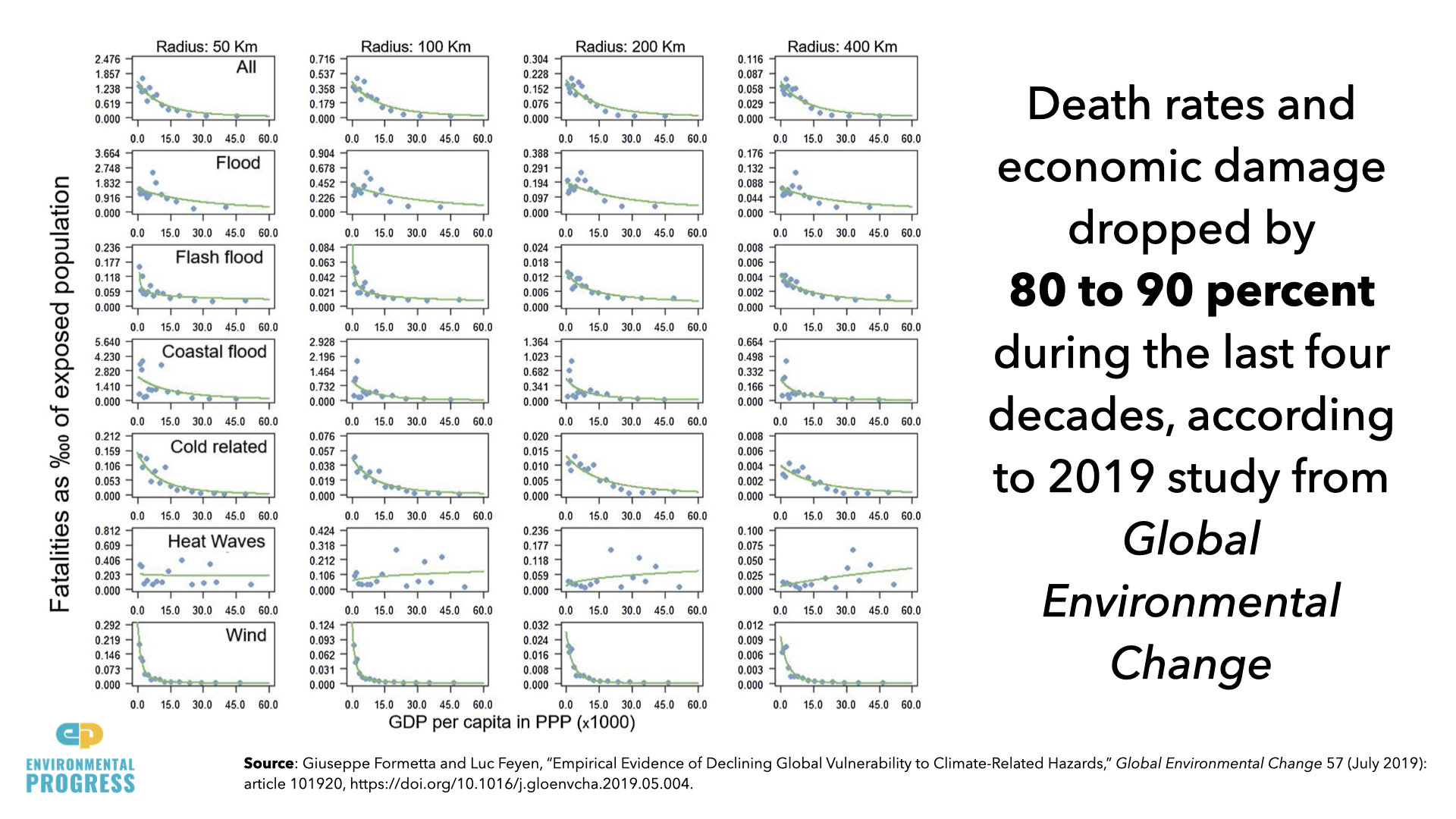

In fact, both rich and poor societies have become far less vulnerable to extreme weather events in recent decades. A 2019 study found that death rates and economic damage dropped by 80 to 90 percent during the last four decades.

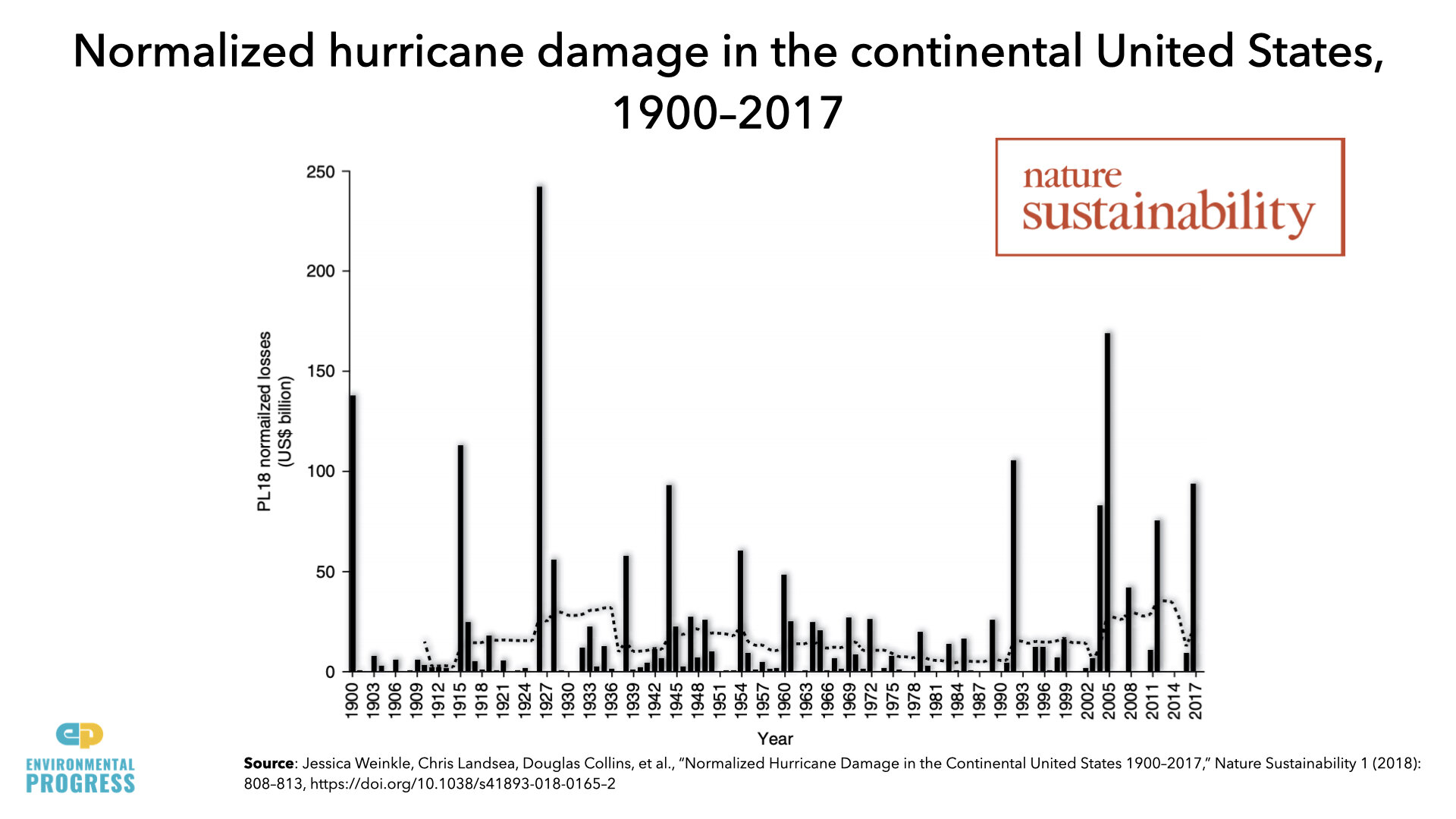

Climate change may be contributing to some extreme weather events, but it has thus far not been a significant factor in economic disaster losses.

What about sea level rise?

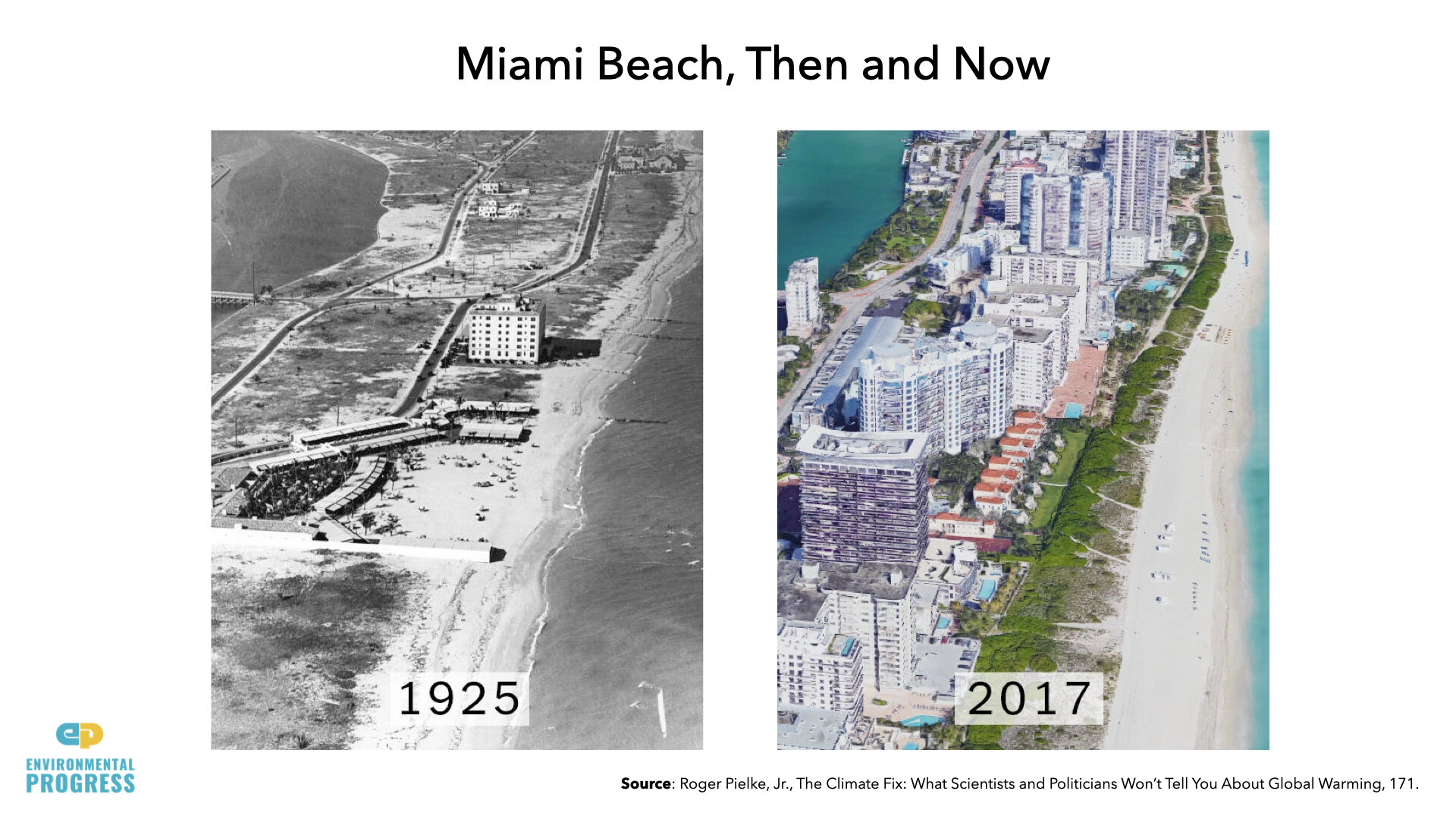

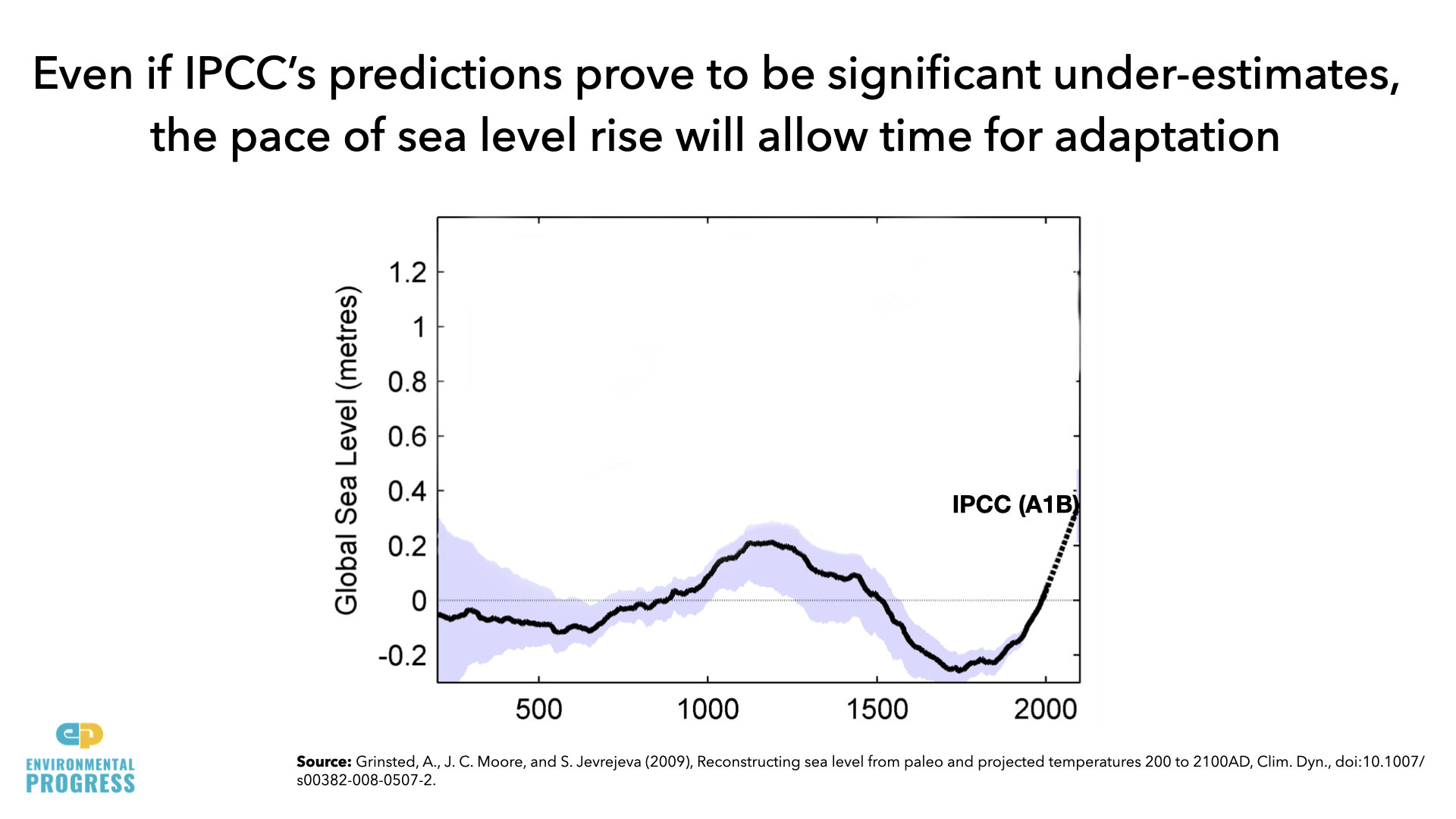

Global sea levels rose 7.5 inches (0.19 meters) between 1901 and 2010. In its most extreme scenario, the IPCC estimates sea levels could rise as much as 2.7 feet (0.83 meters) by 2100. Even if sea level rises at rates estimated by this high-end scenario, societies have ample time for adaptation.

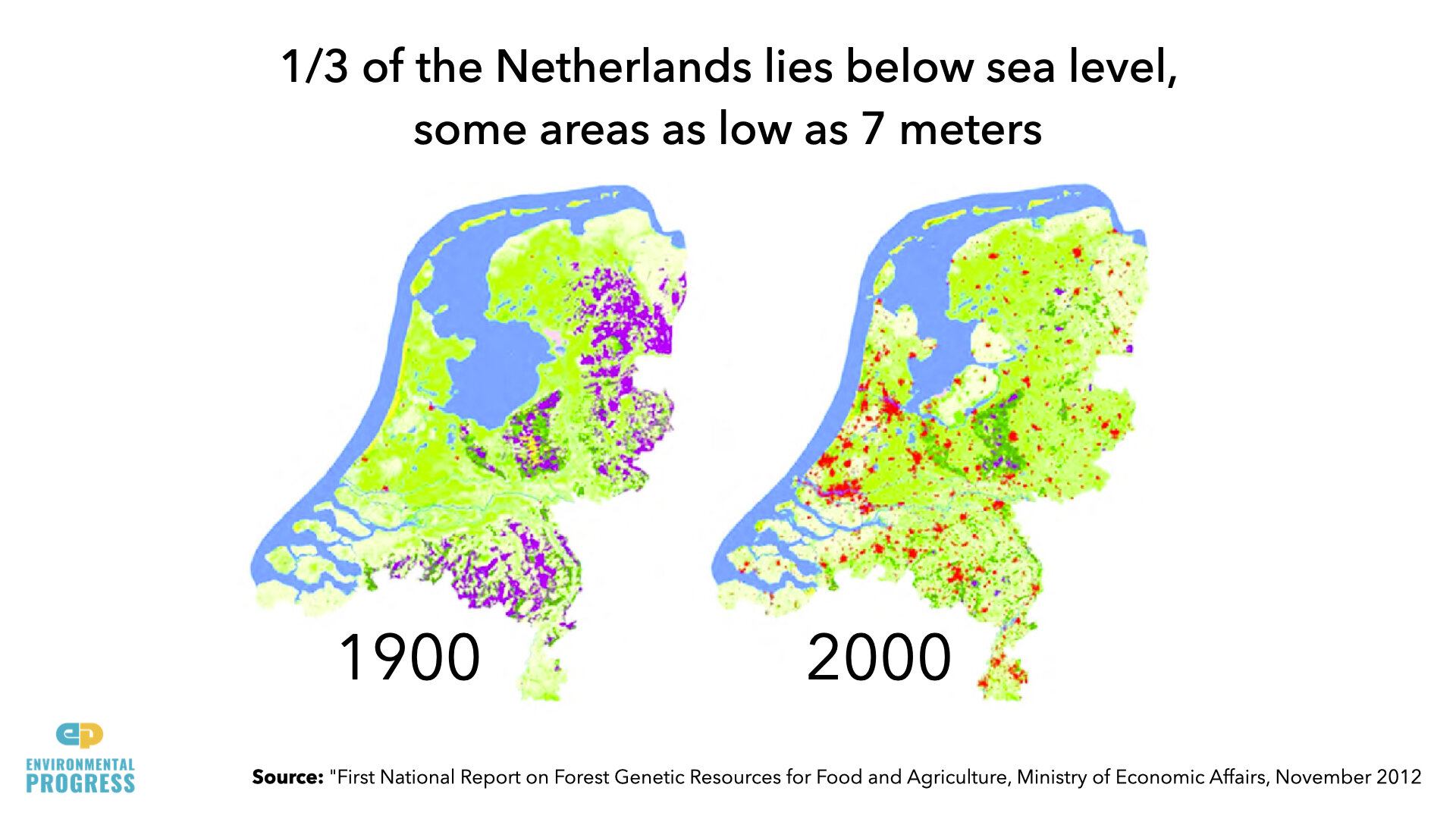

Luckily, we have good examples of successful adaptation to sea level rise. The Netherlands, for instance, became a wealthy nation despite having one-third of its landmass below sea level, including areas a full seven meters below sea level, as a result of the gradual sinking of its landscapes.

And today, our capability for modifying environments is far greater than ever before. Dutch experts today are already working with the government of Bangladesh to prepare for rising sea levels

What about fires?

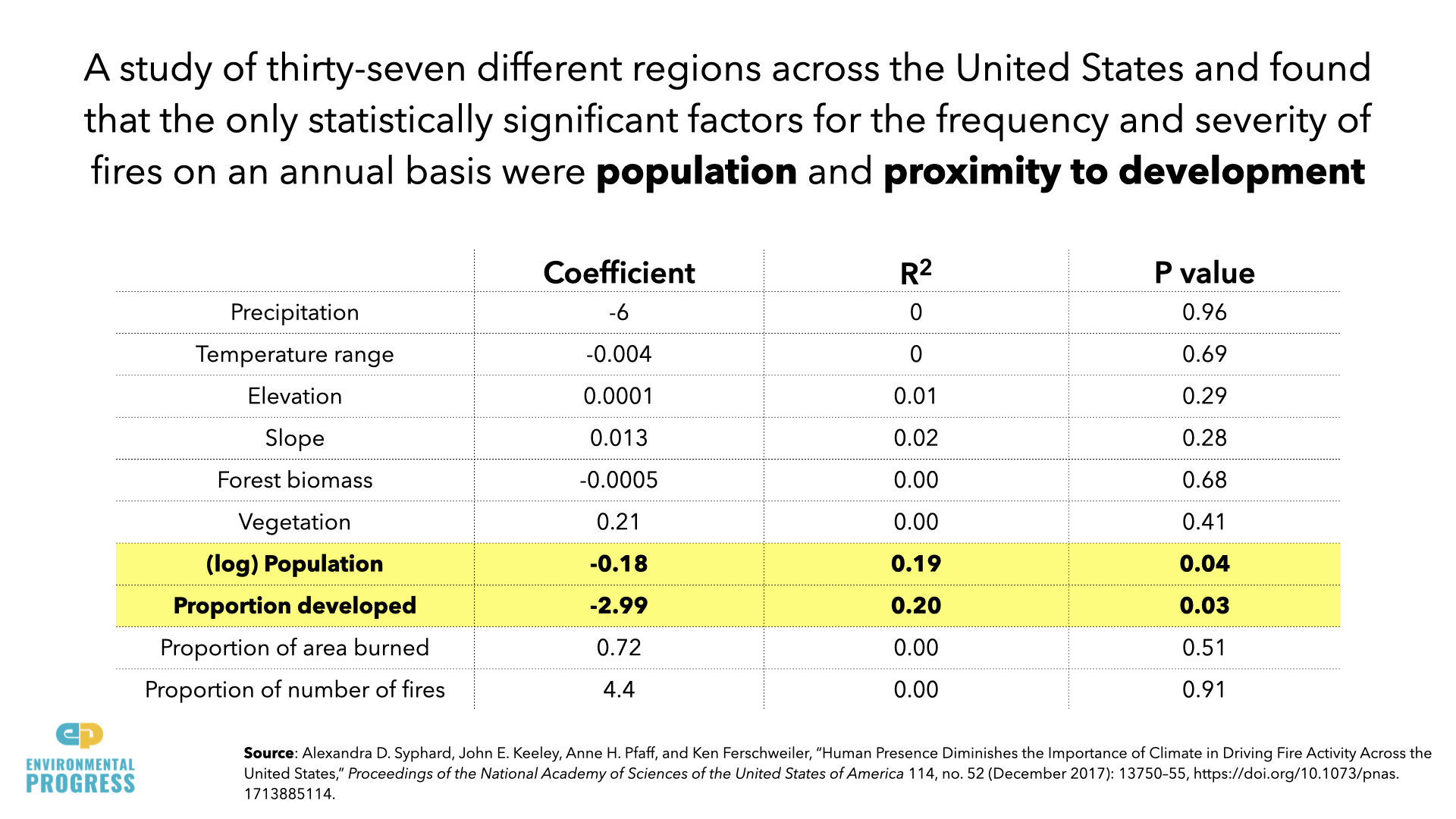

The increasing visibility and media coverage of wildfires certainly makes it seem like fires are getting worse because of climate change. It turns out, however, that other human activities have a much greater impact than greenhouse gas emissions on the frequency and severity of forest fires.

In 2017, a study that modeled thirty-seven different regions across the United States concluded that “humans may not only influence fire regimes but their presence can actually override, or swamp out, the effects of climate.” The study found that the only statistically significant factors for the frequency and severity of fires on an annual basis were population and proximity to development, i.e. how close the fires occurred to homes, businesses, etc.

As for the fires in the Amazon that occurred last year, The New York Times reported, correctly, that “[the 2019] fires were not caused by climate change.”

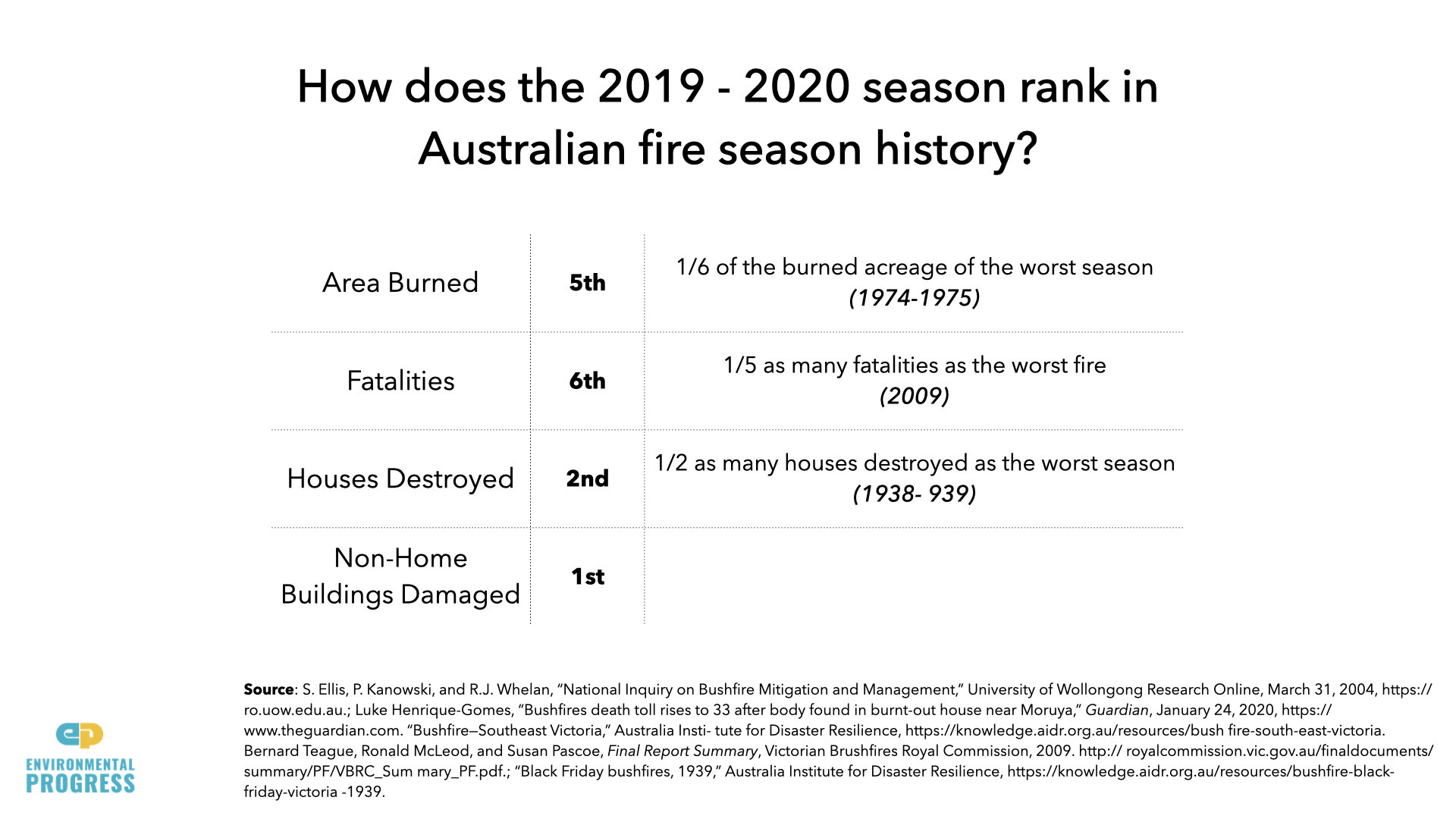

And though the 2019-2020 season of Australian bushfires got a lot of media attention, it was a rather unremarkable year. The 2019-2020 fires ranked:

5th in terms of area burned, with about 1/6 of the burned acreage of the worst season in 1974–1975

6th in fatalities, about 1/5 as many fatalities as the worst fire on record in 2009

2nd in number of houses destroyed, razing about 50% less than the worst year, the 1938–39 fire season

That human activity outweighs climate as a determinant of fire severity is actually good news, because it means places like Australia, California, and Brazil can implement policies that will help reduce the impact of fires going forward.

What about tipping points?

The idea of “tipping points” is that there are certain thresholds in a system that, when exceeded, will lead to major runaway changes. When people talk about tipping points in relation to climate change, they’re referring to the possibility of a rapid, accelerating, and simultaneous loss of Greenland or West Antarctic ice sheets, the drying out of and die-back of the Amazon, and a change of the Atlantic Ocean circulation, to name a few.

Many tipping point scenarios like the ones described are unscientific due to the high level of uncertainty on each and the complexity of the systems themselves. That’s not to say that a catastrophic tipping point scenario is impossible, only that there is no scientific evidence that one would be more probable or catastrophic than other potentially catastrophic scenarios, including an asteroid impact or super-volcanoes.

What about food production? Will climate change make it harder to grow enough food for a rising population?

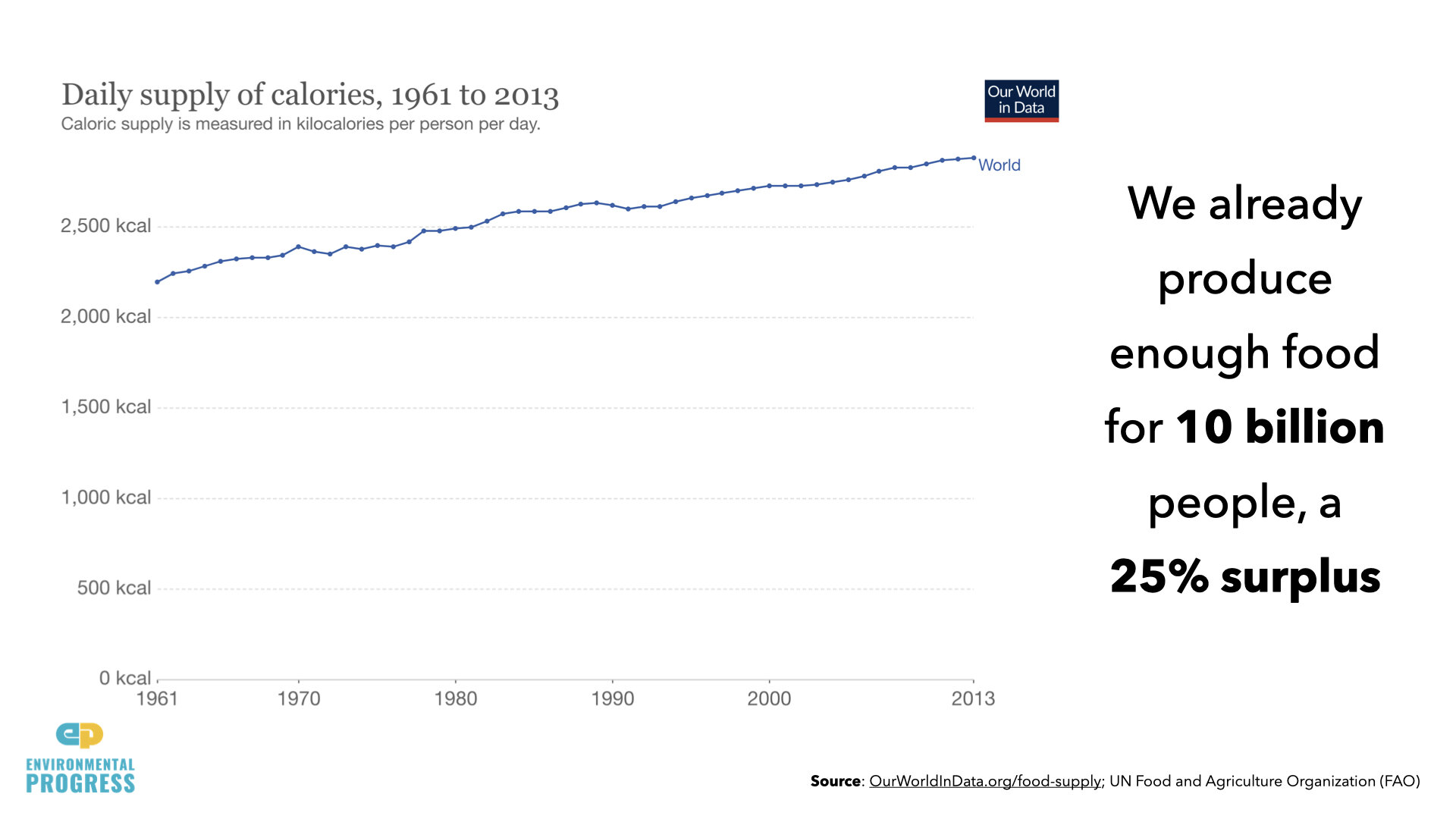

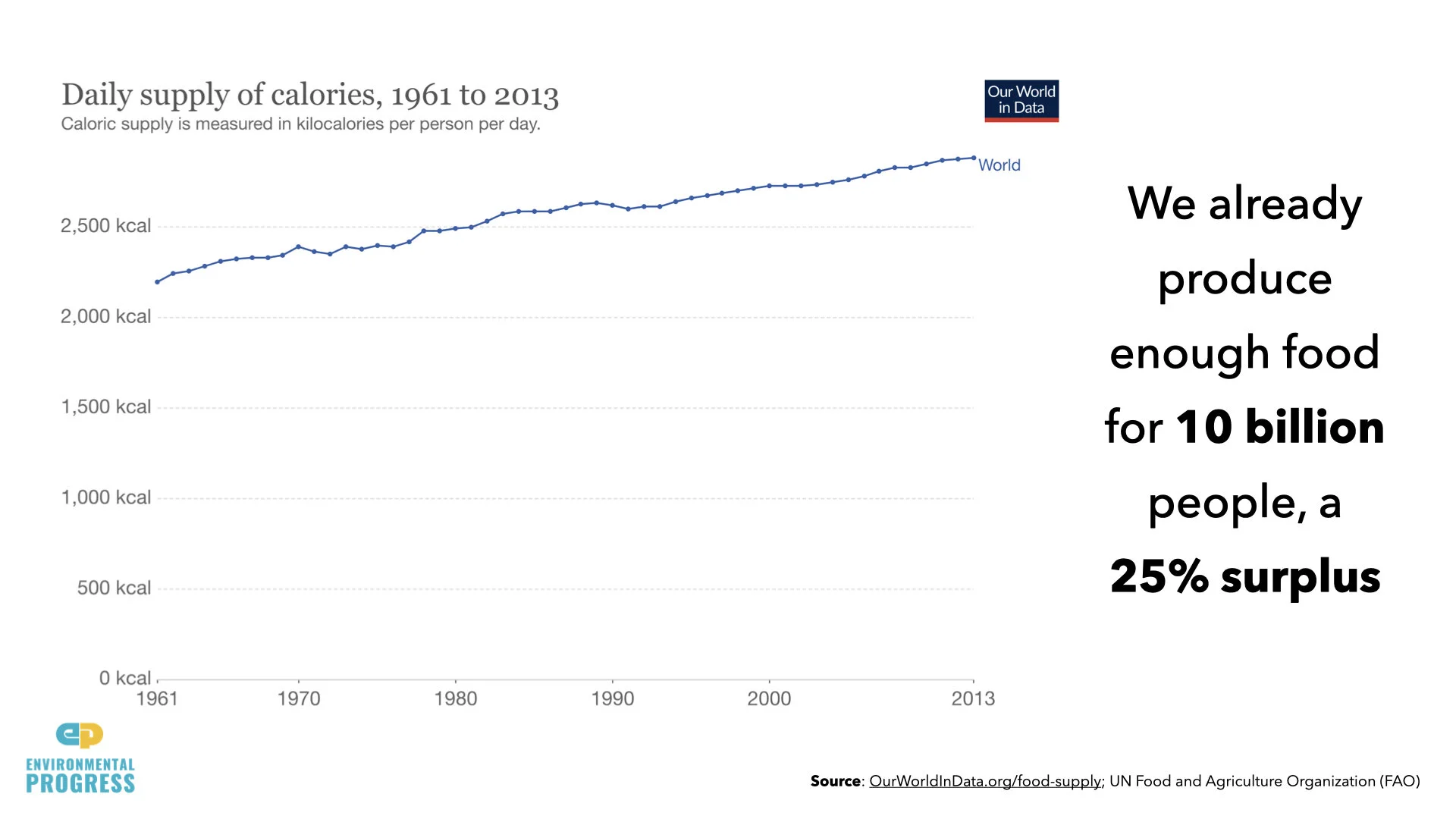

Today, humans already produce enough food for 10 billion people, which is 25% more than we need. And experts believe we will produce even more food in the future despite climate change. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concludes that crop yields will increase significantly under a wide range of scenarios, including significant warming.

Instead, food production will depend more on access to tractors, irrigation, and fertilizer than on climate change. The FAO projects that even farmers in the poorest regions today, like sub-Saharan Africa, may see 40 percent crop yield increases from technology.

If all of this is true, then how will people die from climate change?

Claims that billions or even millions of people will die as a result of climate change are simply not true. Activists who have made these claims are doing so without evidence, and scientists who have suggested this have been discredited.

But aren’t people in poorer countries more vulnerable to climate change than those in wealthy countries?

It’s true, richer countries are more resilient than poorer countries. We should be concerned about the impact of climate change on vulnerable populations, without question.

But people living in impoverished countries are also more vulnerable to the weather and natural disasters today.

Ultimately, economic development and the standard of living will determine how much risk the people in these countries face, not exactly how much the climate changes. For example, it matters less exactly how much rain falls in a village in the Congo if they have proper sewage and water management systems.

Isn’t it better to raise the alarm so people will act?

There is certainly good reason to act on climate change. But making unscientific claims about the seriousness of climate change may do more harm than good.

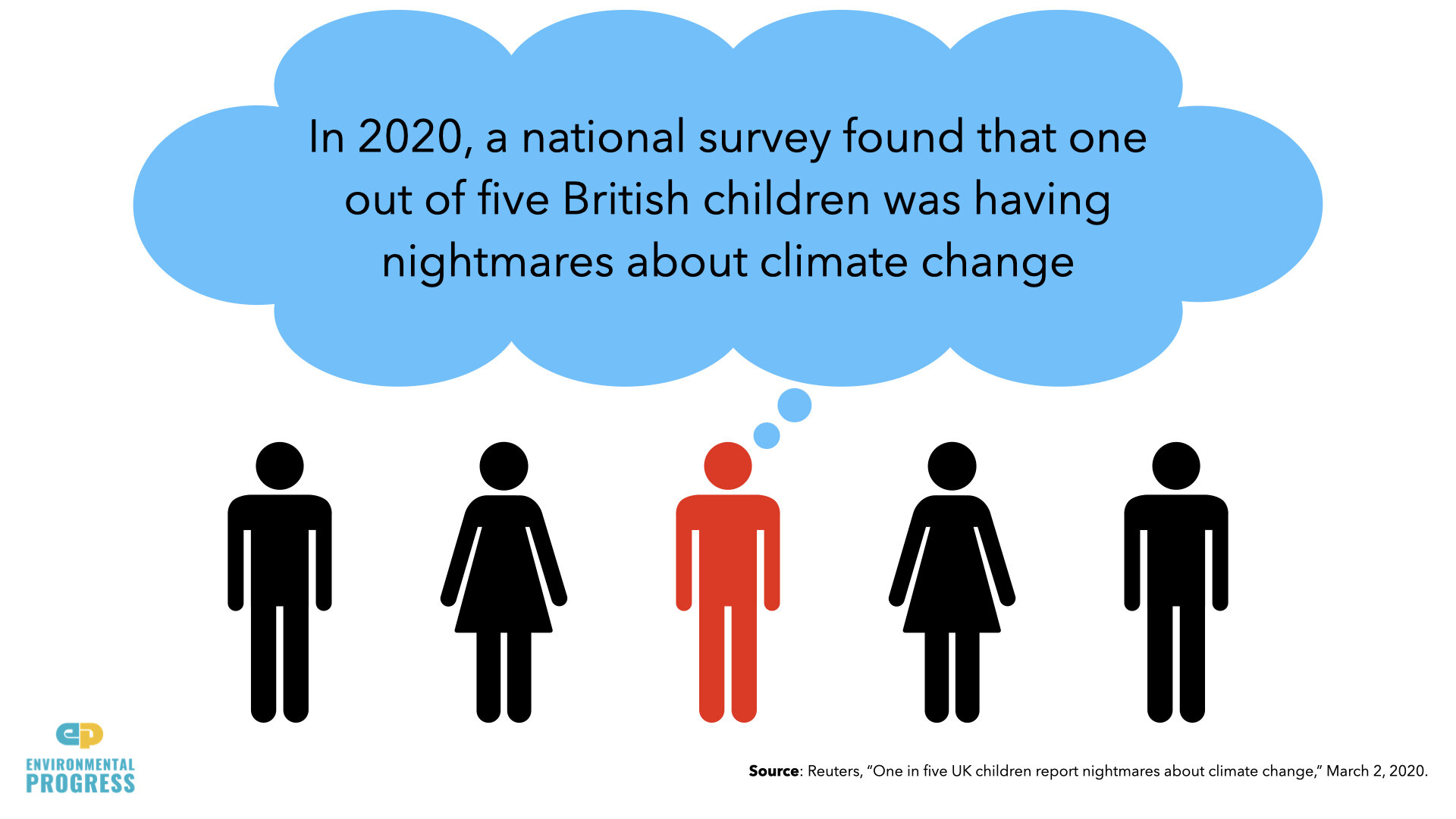

Studies find that climate alarmism is contributing to rising anxiety and depression, particularly among children. In 2020, a large national survey found that one out of five British children was having nightmares about climate change.

Further, setting unrealistic targets and proposing drastic measures may make people skeptical about our ability to deal with climate change at all. This could actually lead to a lack of action.

Then what should we do?

We should continue to work towards reducing our greenhouse gas emissions, largely by decarbonizing our energy sources. But since wealthier countries are more resilient and better able to adapt, we should also focus on making more countries wealthier through economic development.

The good news is that carbon emissions have been declining in developed nations for more than a decade. Most energy experts believe emissions in developing nations will peak and decline, just as they did in developed nations, once they achieve a similar level of prosperity.

As a result, global temperatures today appear much more likely to peak at between two to three degrees centigrade over pre-industrial levels, not four, where the risks, including from tipping points, are significantly lower.