Why I changed my mind about nuclear power: Transcript of Michael Shellenberger's TEDx Berlin 2017

By Michael Shellenberger

Like a lot of kids born in the early 1970s, I had the good fortune to be raised by hippies. One of my childhood heroes was Stewart Brand. Stewart is not only one of the original hippies, he’s also one of the first modern environmentalists of the 1960s and 70s. As a young boy, one of my favorite memories is playing cooperative games that Stewart Brand invented as an antidote to the Vietnam War.

I’m from a long line of Christian Pacifists known as Mennonites. Every August, as kids, we would remember the US government’s atomic bombing of Japan by lighting candles and sending them on paper boats at Bittersweet Park.

After high school, throughout college, and afterwards, I brought delegations of people to Central America to promote diplomacy and peace and to support local farmer cooperatives in Guatemala and Nicaragua.

Over time, as I’ve travelled around the world and visited small farming communities on every continent, I’ve come to appreciate that most young people don’t want to be stuck in the village. They don’t want to spend their whole lives chopping and hauling wood. They want to go to the city for opportunity — at least most of them them do — for education and for work.

What I’ve realized is that process of urbanization of moving to the city is actually very positive for nature. It allows the natural environment to come back. It allows for the central African Mountain Gorilla, an important endangered species, to have the habitat they need to survive and thrive.

In that process you have to go vertical, and so even in places like Hong Kong you can see that with tall buildings they can spare the natural environment around the city.

Of course, it takes a huge amount of energy to go up, and so the big question of our time is how do you get plentiful, reliable electricity without destroying the climate?

I started out as an anti-nuclear activist and I quickly got involved in advocating for renewable energy. In the early part of this century I helped to start a labor union and environmentalist alliance called the Apollo Alliance and we pushed for a big investment in clean energy: solar, wind, electric cars.

The investment idea was eventually picked up by President Obama, and during his time in office we invested about $150 billion to make solar, wind and electric cars much cheaper than they were.

We seemed to be having a lot of success but we were starting to have some challenges. Some of them you’re familiar with. Solar and wind generate electricity in Germany just 10 to 30 percent of the time, and so we’re dependent on the weather for electricity.

There were other problems we were noticing, though. Sometimes these energy sources generate too much power and while you hear a lot of hype about batteries we don’t have sufficient storage even in California, where we have a lot of investment and a lot of Silicon Valley types putting a lot of investment in battery and other storage technologies.

While we were struggling with these problems, Stewart Brand came out in 2005 and said we should rethink nuclear power. This was a shock to the system for me and my friends. Stewart was one of the first big advocates of solar energy anywhere during the early 1970s. He advised Governor Jerry Brown of California.

But he said, look, we’ve been trying to do solar for a long time and yet we get less than a half of a percent of our electricity globally from solar, about two percent from wind, and the majority of our clean energy comes from nuclear and hydro.

And according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, nuclear produces four times less carbon emissions than solar does. That’s why they recommended in their recent report the more intensive use of renewables, nuclear and carbon capture and storage.

Let’s take a closer look at Germany. Germany gets the majority of its electricity and all of its transportation fuels from fossil fuels. Last year Germany got 40 percent of its electricity from coal, 13 percent from nuclear, 12 percent from natural gas, 12 percent from wind, and six percent from solar.

Keep in mind that you don’t just have to go from 18 percent solar and wind to 100 percent solar and wind. To replace the entire transportation sector with electric cars you’d need to go from 18 percent renewables to something like 150 percent. Germany’s done a lot to invest in renewables and innovate with solar and wind, but that’s a pretty steep climb — even before you get to the question of storage.

Let’s look at last year. Germany installed four percent more solar panels but generated three percent less electricity from solar. Even when I’m in meetings with energy experts and I ask people if they can make a guess as to why they think that is, and you’d be shocked by how many energy experts have no idea.

The reason is just that it wasn’t very sunny last year in Germany.

Well, that probably meant that it was windier, right? Because if it’s not as sunny then maybe there’s more wind and those things can balance each other out?

In truth, Germany installed 11 percent more wind turbines in 2016 but got two percent less of its electricity from wind. Same story. Just not very windy.

So then you might think, “Well, we just need to do a lot of solar and wind so that when there’s not a lot of sunlight or wind we can get more electricity from those energy sources.”

That’s what Germany is trying to do. Its plan is to increase the amount of electricity it gets from solar by 50 percent by 2030, which would take you from 40 to 60 gigawatts.

But if you have a year like 2016, you’ll still only be getting nine percent of your total electricity from solar. And this is the biggest solar country in the world. Germany is the powerhouse of renewables.

The obvious response is we’ll just put it all in batteries. We hear so much talk about batteries. You would think that we just have a huge amount of storage.

Environmental Progress took a look at our home state of California and we discovered that we have just 23 minutes of storage for the grid — and to get that 23 minutes you’d have to use every battery in every car and truck in the state. (Which, as you can imagine, is not super practical if you’re trying to get somewhere. And Germany might be a little different but not very different from California.)

Most people are aware that to make this transition to renewables, Germany has been spending a lot more on electricity. And German electricity prices rose about 50 percent over the last 10 years. Today, German electricity is about two times more expensive than electricity is in France.

You might think, look, that’s a small price to pay to deal with climate change. And I would agree with that. Paying a bit more for energy — at least for those of us in the rich world — is a decent thing to do to avert the risk of catastrophic global warming.

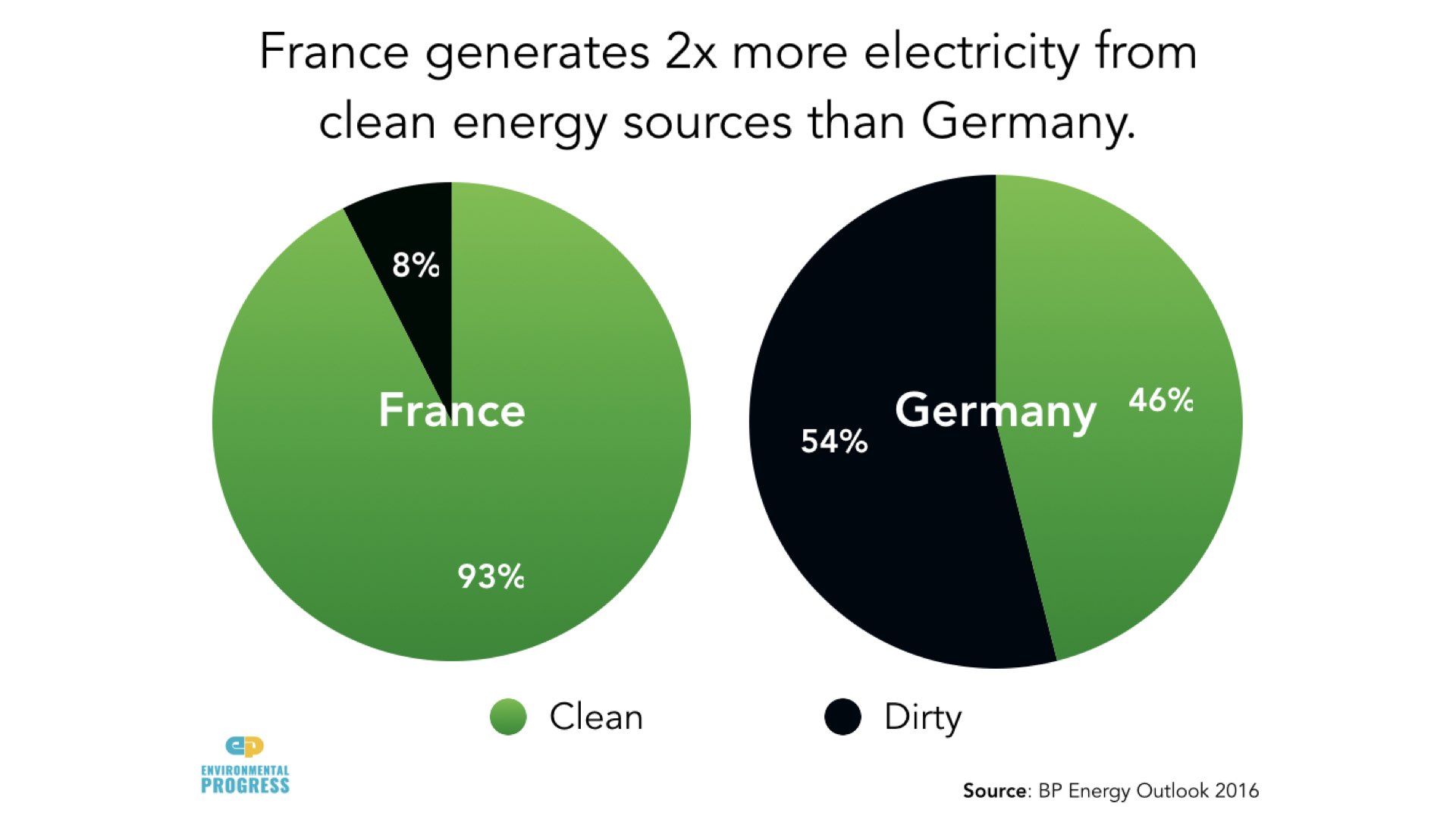

But when you compare French and German electricity, France gets 93 percent of its electricity from clean energy sources, mostly hydro and nuclear while Germany gets just 46 percent, or about half as much clean energy.

Here’s the shocking thing: German carbon emissions have gone up since 2009, and up over the last two years, and may go up again this year. And while German emissions have gone down since the 1990s, most of that is because, after reunification, Germany closed the inefficient coal plants from East Germany. Most of its emissions reductions are just due to that.

Let’s look at last year. One of the ways you can reduce emissions quickly is by switching from coal to natural gas, which produces about half as much emissions. Coal to gas switching would have resulted in lower emissions except for the fact that Germany took nuclear reactors off-line. And when it did that, emissions went up again.

There’s still question about the future: if we do a lot of solar and wind, won’t it all work itself out?

One of the biggest challenges to solar and wind has come from somebody in Germany who is not a pro-nuclear person at all. He’s an energy analyst and economist named Leon Hirth. What he finds is that the problem I described earlier — where you have too much solar or wind and you don’t know what to do with it — reduces their economic value.

The value of wind drops 40 percent once it becomes 30 percent of your electricity, Hirth finds, and the value of solar drops by half when it gets to just 15 percent.

One of the things you hear is that we can do a solar roof fast — just one day to put up the thing — whereas it takes five or ten years to build a nuclear plant. And so people think that if we do solar and wind we can go a lot faster.

But the speed of deployment was the subject of an important article in the journal Science last year, which was coauthored by the climate scientist James Hansen. They found that even when you combine solar and wind you just get a lot less energy than when you do nuclear. That goes for Germany as well as the United States. They just compared ten years of deployment for the two technologies and it’s a stark comparison.

Well, I can tell what you’re thinking, because it’s what I was thinking: it sounds like I might need to rethink my views of nuclear power. But what about Chernobyl? What about Fukushima? What about all the nuclear waste? Those are really reasonable questions to ask.

When I was starting to ask them, there were other people who were starting to change their minds. One of the ones I was most impressed by, and who was very influential, was George Monbiot.

Monbiot wrote a column shortly after Fukushima where he went through the scientific research on radiation and concluded, “The anti-nuclear movement to which I once belonged has misled the world about the impacts of radiation on human health.”

I write some pretty harsh things sometimes, but this was a pretty strong column. He was talking to a lot of scientists who study radiation.

One top British scientist who studies radiation is Gerry Thomas. She started something called the Chernobyl Tissue Bank out of her concern for the accident. She’s a totally independent professor of pathology at Imperial College in London.

I called her and said, “I’d like to present on the science of radiation but I’m not a radiation scientist, so can I just steal your slides? If you let me, I’ll put your picture on them.”

The first thing she points out is that most ionizing radiation — that’s the kind of radiation that is potentially harmful that comes from a nuclear accident — is natural.

I was like, “That sounds alright. I like natural foods. Natural radiation from hot springs.”

Gerry said, “No, actually, natural radiation is just as potentially harmful as artificial radiation.”

What’s striking is that the total amount of ionizing radiation we’re exposed not just from Chernobyl and Fukushima but all of the atomic bomb testing in the sixties and 70s totals just 0.3 percent. Most of the radiation we’re exposed to comes from the earth, the atmosphere, and the buildings around us.

Let’s look at the big one: Chernobyl. This was the event that led me to be anti-nuclear and become an anti-nuclear activist.

The United Nations has overseen these very large research efforts involving hundreds of scientists around the world who do this research. So the possibility of somebody fudging the data or covering something up is pretty low in that environment, because there are so many credible scientists at different universities doing the research.

This was a pivotal moment for me. Chernobyl is the worst nuclear accident we’ve ever had. Some people say it’s the worst accident we’ll ever have. I don’t need to make a statement that strong. But they literally had a nuclear reactor without a containment dome and it was on fire. It was just raining radiation down on everybody. It was a terrible accident.

But when they start counting bodies, what they come up with is 28 deaths from acute radiation syndrome, 15 deaths from thyroid cancer over the last 25 years. As horrible as it sounds, thyroid cancer is the best cancer to get because hardly anybody dies from it. It’s highly treatable. You can have a surgery to remove the thyroid gland and take thyroxine, which is a synthetic substitute. In fact, most of the people who died were in remote rural areas where they couldn’t get the treatment they needed.

If you take the 16,000 people who got thyroid cancer from Chernobyl, they estimate 160 of them will die from it. And it’s not like they’re dying of it right away. They’ll die from it in old age. That’s not to say it’s okay, but it’s to put it in some context.

And there’s no evidence of any increase in thyroid cancer outside of the three nations most affected, Russia, Ukraine and Belarus.

There’s no evidence of an effect by Chernobyl on fertility, birth malformations, or infant mortality; nor for causing an increase in adverse pregnancy outcomes or still births; nor for any genetic effects.

I think this last one is the most striking thing: there’s no evidence of any increase in non-thyroid cancer including among the cohort who put out the Chernobyl fire and cleaned it up afterwards.

I’m still surprised by this finding, and so I put the link to the web site on that slide, because I don’t think you should take my word for it. Reading about Chernobyl was, for me, a big part of changing my mind.

What about Fukushima? It was the second worst nuclear disaster in history and a lot smaller than Chernobyl. There have been no deaths from radiation exposure, which is pretty amazing. Meanwhile, 1,500 people died being pulled out of nursing homes, hospitals — it was insane. It was a panic. The Japanese government shouldn’t have done that. It violated every standard of what you’re supposed to do an accident. You’re supposed to shelter-in-place. In fact, by pulling people out of their homes and moving them around outside they actually exposed more people to more radiation.

And you have to put that in comparison of the other things that were going on, like the 15,000 to 20,000 dying instantly from drowning — pinned down by many different technologies, by the way — from that tsunami.

So while there was no increase in thyroid cancer, there was the stress and fear from believing you were contaminated despite the evidence showing that that wasn’t the case at all.

Some scientists did an interesting study. They took a bunch of school children from France to Fukushima and had them wear dosimeters, which is what we call geiger counters now.

You can see here that when those kids go through the airport security system their radiation exposures spiked. When they flew from Paris to Tokyo on the airplane their radiation exposures spiked. They went through the French embassy’s security system their radiation exposures spiked.

When they went to the city of Tomioka, which received a lot of radiation from the accident, it was just a tiny blip compared to the security systems.

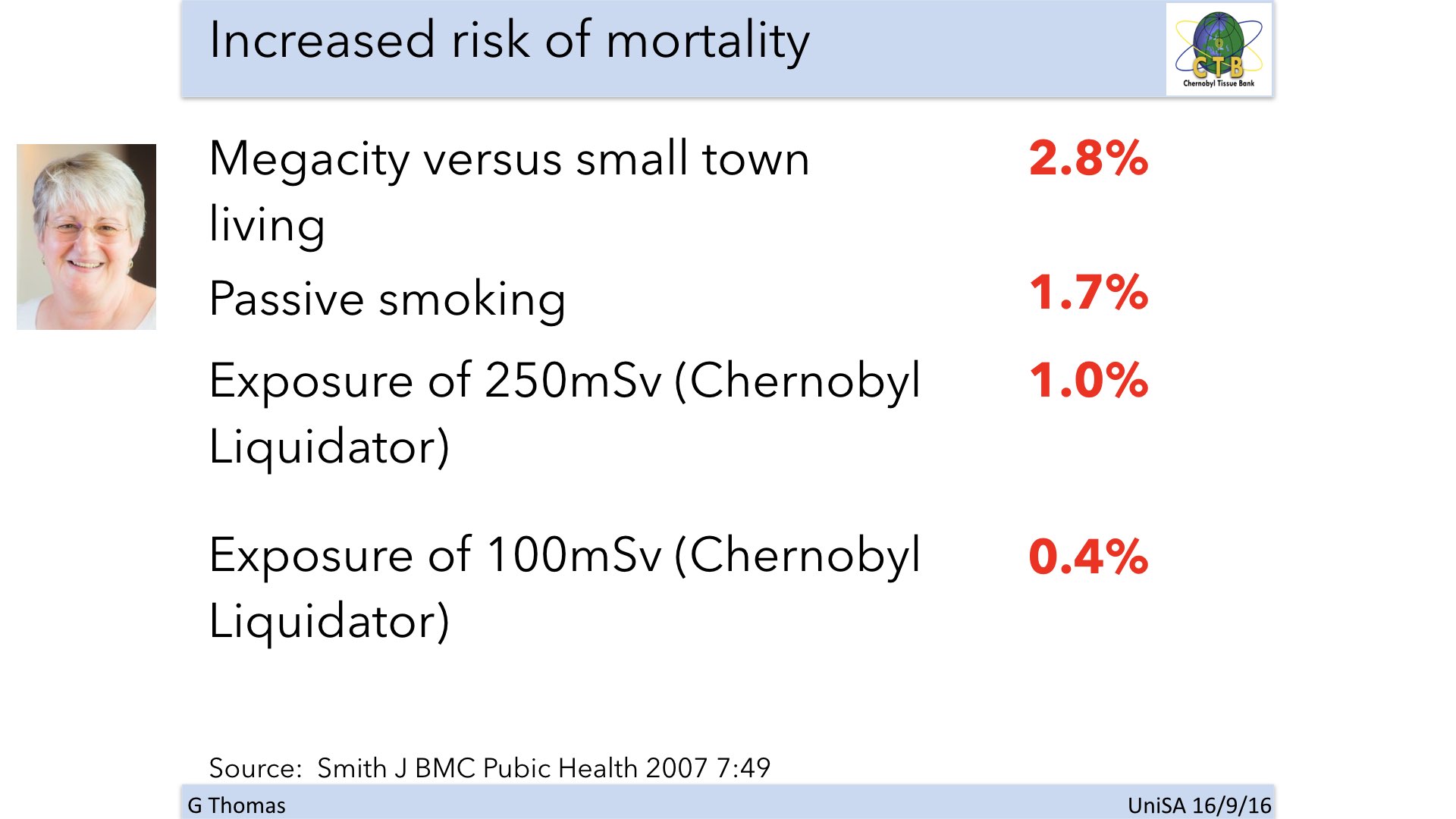

Let’s put this in an even larger context. If you live in a big city like London, Berlin, or New York, you increase your mortality risk by 2.8 percent, just from air pollution alone. If you live with someone who smokes cigarettes your mortality risk increases 1.7 percent.

But if you were someone who cleaned up Chernobyl, your mortality risk increased just one percent. That’s just because there wasn’t as much radiation exposure as people thought.

I’m from the state of Colorado in the United States where we have an annual exposure to radiation about the same as what people who live around Chernobyl get.

This is really basic science and is right there on their web site but nobody knows it. Only eight percent of Russians surveyed accurately predicted the death toll from Chernobyl, and zero percent accurately predicted the death toll from Fukushima.

Meanwhile, there are seven million premature deaths per year from air pollution and the evidence against particulate matter only gets stronger. That’s why every major journal that looks at it concludes that nuclear is the safest way to make reliable electricity.

All of this leads to an uncomfortable conclusion — one that the climate scientist James Hansen came to recently: nuclear power has actually saved 1.8 million lives. That’s not something you hear very much about.

What about the waste? This is the waste from a nuclear plant in the United States. The thing about nuclear waste is that it’s the only waste from electricity production that is safely contained anywhere. All of the other waste for electricity goes into the environment including from coal, natural gas and — here’s another uncomfortable conclusion — solar panels.

There’s no plan to recycle solar panels outside of the EU. That means that all of our solar in California will join the waste stream. And that waste contains heavy toxic metals like chromium, cadmium, and lead.

So how much toxic solar waste is there? Well, to get a sense for that, look at how much more materials are required to produce energy from solar and wind compared to nuclear. As a result, solar actually produces 200 to 300 times more toxic waste than nuclear.

What about weapons? If there were any chance that more nuclear energy increased the risk of nuclear war, I would be against it. I believe that diplomacy is almost always the right solution.

People say what about North Korea? Korea proves the point. In order to get nuclear power — and it’s been this way for 50 years — you have to agree not to get a weapon. That’s the deal.

South Korea wanted nuclear power. They agreed not to get a weapon. They don’t have a weapon.

North Korea wanted nuclear power. I think they should have gotten it. We didn’t let them have it, for a variety of reasons. They got a bomb. They are testing missiles that can hit Japan and soon will be able to hit California.

So if you’re looking for evidence that nuclear energy leads to bombs you can’t find it in Korea or anywhere else.

Where does that leave us? With some more uncomfortable facts. Like if Germany hadn’t closed its nuclear plants, it’s emissions would be 43 percent lower than they are today. And if you care about climate change, that’s something you at least have to wrestle with — especially in light of the facts I’ve presented on the health impacts of different energy sources.

I’d like to close with a quote from somebody else who changed his mind about nuclear power, and somebody else who was a huge childhood hero for me, and that’s Sting: “If we’re going to tackle global warming, nuclear power is the only way to generate massive amounts of power.”

Thank you for listening.