The Future of Nuclear

by Michael Shellenberger

In 2016, pro-nuclear advocates won our first victories against the anti-nuclear Goliath, saving nuclear plants from closure in Switzerland, Illinois, New York and Sweden.

But the anti-nuclear establishment quickly struck back with a series of victories resulting in announced nuclear plant closures and cancellations in New York and Taiwan, adding to the heavy losses pro-nuclear advocates have sustained in California, Germany and Japan.

Now, in the wake of a financial crisis resulting from construction delays and cost overruns at two U.S. nuclear plants, the American nuclear giant Westinghouse has announced it might go bankrupt.

And South Korea, one of the great hopes for a global nuclear renaissance, appears poised to elect as president a man who is campaigning to shutter all of that nation’s nuclear power plants.

After I described just how desperate the situation facing nuclear is, a friend last week replied, “Knowledge is the antidote to fear.”

He told me a story about the operator of Fukushima Daiini — a nuclear plant down the road from Fukushima Daiichi, where three reactors melted down.

Daiini faced similar problems as Daiichi, but its operator responded differently. “He gathered everyone together and started putting information up on a white board,” my friend said.

“They got clear about what was going on. They kept the information flowing," my friend explained. "And that allowed them to save the plant.”

The Antidote to Fear

Last year, EP and I were the first to note that the share of global electricity coming from clean energy had — against the hype — actually declined, in part due to the closure and cancellation of nuclear plants.

And in recent months, EP’s quantitative analyses of the impact of closing nuclear plants on air pollution in California and Germany were picked up by news media from around the world.

Even so, if you listen to some within the industry and government, nuclear’s doing okay. They note that there are more plants are under construction than at any time in the last two decades, and that there has been a proliferation of nuclear start-ups.

My colleagues and I wanted to get an accurate account of nuclear status based on a nation-by-nation, plant-by-plant assessment, and so over the last three months we researched and have now rated for the likelihood of opening and closing:

· Every operating nuclear plant in the world;

· Every nuclear plant being built;

· Every nuclear plant being proposed.

We conclude that if nothing changes, more nuclear plants are likely to close than open between now and 2030.

If our forecast is correct, it would be a continuation of nuclear’s absolute decline since 2006, and an acceleration of its relative decline (as a share of total global electricity) since 1996.

When nuclear plants are cancelled or closed, they are replaced almost entirely with fossil fuels, and so this is bad news for clean air and the climate.

We are calling our ongoing assessment of progress being made toward meeting the goals of universal prosperity and environmental protection the “Energy Progress Tracker” (EPT).

This is not an academic exercise for us. EP is doing this because we want to prevent nuclear plants from closing and increase the number of plants opening.

As advocates for nuclear, EP could have a bias. Consciously or unconsciously, we might want to show that the situation is worse than it is, or better than it is, in order to raise fears or hopes, and money, or to motivate some other kind of action.

At the same time, we have an incentive to maintain our reputation for accurate, honest and cutting-edge analyses.

Whatever the case, in service of accuracy, honesty and transparency, we are publishing our national and plant-specific assessments, and inviting comments, particularly from those with local or national knowledge.

Going forward, EP will adjust our rankings in real-time according to real-world events and keep track of how our rankings changed over time, with accompanying explanations for why they changed.

For example, if presidential front-runner Moon Jae-in is defeated on May 9, we would likely change our assessment of South Korean nuclear.

No Nukes? No Climate

Over the last decade and a half I have been critical of those who claim the world will end imminently if we don’t drastically downscale our lives to save the climate. That’s bad religion and politics — authoritarian and demotivating.

Now, with my recent focus on nuclear power for ending poverty and mitigating climate change, a few friends have asked whether my views on climate have changed. Am I more worried about climate than I was before?

The short answer is yes. If nuclear plants were being scaled up globally at the rate France and Sweden did in the 1970s and 1980s, then I would probably be a “lukewarmer” — somebody who believes that humans are causing global warming, but that it probably won’t get too hot, or be that bad.

Maisha, the gorilla, was orphaned after her parents and family were killed by charcoal mafia in Congo. The Indonesian girl is the daughter of Matun, who I met while they were gathering snails for sale. Both photos are from "The Story of Environmental Progress," the current gallery exhibit at our headquarters in Berkeley.

But given nuclear’s rapidly accelerating decline, I am now a “climate alarmist” — somebody who believes that if the situation doesn’t change, we are headed in a dangerous direction.

That doesn’t mean making everyone poor or even slowing growth. On the contrary: France enjoys some of the cheapest, and cleanest, electricity in Europe. And the right to cheap electricity is, for all of us at EP, a fundamental human right.

But if nuclear’s fortunes are not reversed, then the chances of preventing very large temperature increases — without using extreme measures, like deliberately trying to cool the planet — drop close to zero.

The truth about nuclear is quite simple. Only nuclear power can lift all humans out of poverty without cooking the planet, or keeping cities like Delhi and Beijing caked in deadly particulate matter.

Coal and fossil fuels can lift people out of poverty, but at the cost of hammering the environment.

Solar and wind barely made up half of nuclear’s seven percent decline as a share of global electricity. It will make up even less over the next 10 years.

Solar and wind are too diffuse and not reliable enough to power factories and cities, and thus cannot lift people out of poverty nor reduce emissions from fossil fuel-powered electrical systems more than only modestly.

Hydro can lift people out of poverty and is low-carbon, but it’s limited — most rich world rivers are over-dammed.

Bluntly, renewables are no substitute for either nuclear or fossil fuels.

Spraying sulfur particles into the atmosphere can temporarily cool the earth but not reduce humankind’s negative environmental impact or lift all people out of poverty. (Plus, it could result in world war, so there’s that to worry about.)

By contrast, everything is in place to just build more nuclear plants. The nuclear plants we have are more than fine — they are great. They are the safest way to make reliable electricity. They use the least amount of natural resources and produce the least amount of waste. And they are long-term investments that can last for 60, 80 and maybe 100 years.

Yes, they require a lot of up-front capital. But that’s what World Bank loans are for.

Yes, they can take many years to build. But at the end of the project you have power to provide for millions — not thousands.

Could future nuclear plants be cheaper and better? Sure — the key is standardization, which allows workers to gain experience building and operating plants.

Why then aren’t we doing it?

Why Nuclear is in Crisis

Outside a few parts of the United States, nuclear plants are threatened with closure for underlying cultural, ideological, and political reasons — not technological or economic ones.

Low natural gas prices have hurt nuclear plants in the Midwest and some of the Northeast but not in the South, thanks to its regulated utilities and largely pro-nuclear culture.

In California and New York, nuclear plants are being shut down by anti-nuclear groups NRDC, Sierra Club and EDF, which are funded by financial interests that stand to benefit from closing nuclear plants.

Anti-nukes are working hand in glove with Governors Jerry Brown and Andrew Cuomo — both of whom have close associates under federal criminal investigation for their roles in killing nuclear plants.

And fear-mongering, not poor economics, is similarly behind attempted nuclear plant closures in Korea, Taiwan, Japan, Germany, Switzerland and Sweden.

Moreover, in Japan, Korea, Taiwan and many other nations, nuclear is not only cheaper than natural gas and petroleum but cheaper even than coal.

And even in the American Midwest and Northeast, nuclear plants have been at very high risk of closure because they’ve been forced to pay an economic penalty, and an oversupplied market, resulting from federal subsidies — now a quarter century old — to wind developers, and from their exclusion from state clean energy mandates.

Nor is the economics of nuclear much of an obstacle when it comes to building new nuclear plants.

Korea’s national utility is building cheap nuclear power plants in the United Arab Emirates thanks to its strong experience building standardized plants back in Korea.

The same is true in China where new nuclear plants are often cheaper than new coal plants.

In Vietnam and South Africa, nuclear could be as cheap as coal, without even factoring in the tens of thousands of additional deaths that will result from coal pollution.

One big problem is inadequate financing. International development banks like the World Bank are headed by people who fear nuclear power, and believe the world can be powered on solar panels and wind turbines.

Lack of financing for nuclear also forces nations to do the opposite of what works to make nuclear cheap. Both the UK and India — two nations that couldn’t be more different — are seeking to build multiple nuclear plants with totally different designs.

That could change, and should. It will require pro-nuclear advocates in those countries to speak out with clarity about what matters.

It’s understandable that some pro-nuclear advocates are so discouraged by the current crisis that they wish for technological breakthroughs that will somehow reduce public fear, or significantly lower costs.

But the record is clear. The only way we know how to significantly reduce nuclear costs, and improve safety, is through the experience of building, operating and regulating the same standard design.

That doesn’t mean we shouldn’t test new designs. We should. New nuclear plants may prove, after a decade or so of operating, to be even better than today’s plants.

But for either deployment or demonstration, we are going to need to confront — and overcome — the real reason that nuclear energy is in crisis.

Witches in the Reactor

Two weeks ago, I received an invitation to travel to Taiwan from a group of pro-nuclear environmentalists and students to speak out in defense of that nation’s nuclear plants.

The situation sounded desperate. A famous political activist had successfully demonized nuclear after the Fukushima accident, and pro-nuclear forces were demoralized.

Taiwan has a new, large and almost fully-built nuclear plant that the government refuses to open.

“They are going to burn coal instead,” the Taiwanese activists told me. “But the politicians say they won’t burn coal or use nuclear.”

I told them that in California, the Governor and his men are killing our nuclear plants by misleading people into believing nuclear is something it's not.

"Like it's witches," I complained.

“That’s what people here say!" one of them said. "That it’s witches!”

I laughed. Fear of nuclear is the same everywhere.

I was blunt. “I can go to Taiwan but I can’t save Taiwan’s nuclear plants,” I told them. “But you guys can.”

I invited them to attend a “Futures of Nuclear” meeting in our new headquarters in Berkeley next month to plot strategy with other pro-nuclear leaders. They agreed.

Our new Taiwanese colleagues will be joining pro-nuclear rebels and allies from Germany, Japan, China, Switzerland, Britain, India, the United States, and, I hope, from Belgium, France and South Africa.

There is hunger for hope — and change. My article last month was translated into French and Chinese and circulated among industry leaders, many of whom will also be joining us in Berkeley.

But if we are to make a comeback, we have to confront reality. Almost all of nuclear’s problems — including the ones that have been self-inflicted — come from anti-nuclear advocates who lie to journalists, policymakers and the public, and manipulate their fears.

I know from experience. I was made to fear nuclear, and then I scared others into fearing it.

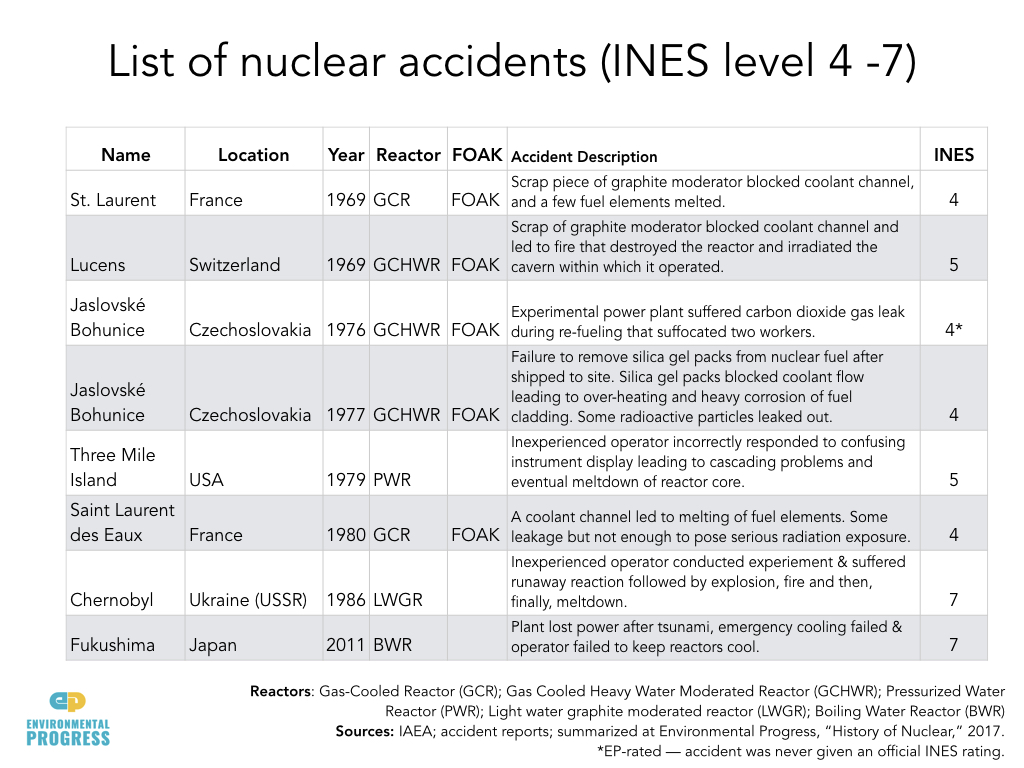

But knowledge was the antidote to my fears. For me, it was learning more about nuclear accidents that finally convinced me nuclear was the best way to make electricity.

Over the last year, EP and our allies, many of whom also used to be anti-nuclear, have dramatically weakened the grip of anti-nuclear forces over the discourse.

It has become increasingly unacceptable for supposed climate activists to attack nuclear power — which is why Bill McKibben, Al Gore, Mike Brune, Ralph Cavanagh, Fred Krupp and Hal Harvey aggressively duck the issue when someone confronts them about it.

And the idea that we can replace fossil fuels and nuclear with solar, wind and dams is increasingly viewed as about as credible as replacing vaccines and antibiotics with homeopathy and acupuncture.

My Taiwanese friends asked me who they should send to our meeting in Berkeley.

“Send somebody has the guts to stand up to the fear mongers,” I said. “Send people who aren’t afraid to debate with powerful people.”

“We have two people!” they said.

One is an environmentalist from the Left, they explained, and the other is a national security expert from the Right.

Perfect, I said. If history’s any guide, that could be a winning combination.

EP is Open

With this post I am excited to announce the opening of EP’s headquarters, which include a gallery, gift shop and event space.

We created EP to be base camp for the global pro-nuclear movement. All are invited to visit us — including our opponents.

I am also happy to introduce EP’s new staff and fellows: Minshu Deng, Mark Nelson, Jenny Woo, Cindy Chou, Jemin Desai, Kylie Feger, John Lindberg, Grace Pratt, Arun Ramamurthy, Pavel Velkovsky, and Daphne Wilson.

When we founded EP last year we settled on two core values: caring and fairness.

EP is now adding openness as our third core value because we believe that achieving our mission requires it.

There is a paradox here because advocacy also requires certainty. When one acts, or advocates that others act, one must have a significant amount of certainty that one is right.

But I know from experience of having been wrong (more than once, and in more than one way) about nuclear, that EP needs to make a practice of challenging our own assumptions.

When I offered the job to Mark, a former Breakthrough Generation Fellow, last summer, I told him that if he ever discovered that solar and batteries were cheaper, cleaner or otherwise better than nuclear power, he had to tell me at once, or I would fire him.

EP Staff members Jenny Woo (second from left, seated), Mark Nelson (standing), and Minshu Deng (laughing).

Later Mark told me that it was at that moment he decided to take the job. He went on to take the lead in creating the Energy Progress Tracker.

There is another reason for choosing openness as a core value: it signifies EP’s commitment to (relatively) open borders for both people and things.

I say relatively because nations have a right to decide who comes in and out, and developing nations often must protect what Alexander Hamilton called their “infant industries” from developed global competitors.

But for the most part, EP believes a positive future requires we keep our doors open to foreigners without regard for race or religion. We believe that rising global economic growth and trade is, on balance, positive.

Of course, we could be wrong. If so, we hope to be the first to know it.

More often than not, we will need to gain comfort acknowledging and acting within some amount of uncertainty.

Some of the best analyses of nuclear’s fortunes over the last year came from Bloomberg New Energy Finance. That was a surprise for me because I have criticized them in the past for their misleading depictions of the growth of solar and wind — namely, not factoring their unreliable and low frequency of generation into calculations of their cost.

But Bloomberg has now produced a graph that makes the seemingly opposite mistake of industry and government analysts by suggesting that nuclear will definitely decline in the United States.

Why is this misleading? Because it suggests there is only one future. In truth, there are many possible futures.

It is misleading because it suggests false certainty about the future, and in that way it is making the same mistake as those presenting a rosy picture of nuclear’s future.

The problem isn’t that Bloomberg is showing nuclear’s potential decline, but that it’s not also showing nuclear’s potential increase, masking the reality that multiple “futures” are possible.

Not only are they possible, they are creatable. We can grow and shrink the bars in our chart of nuclear at risk.

This is not an idle claim. Having gone nation-by-nation, and plant-by-plant, it’s clear to all of us at EP that the future of nuclear power is open.

The Future of Nuclear

Last June, Pacific Gas and Electric announced it would close California’s last nuclear power plant, a decision that will increase air pollution for poor communities near fossil fuel power plants, and increase global warming.

In response, I announced I would commit civil disobedience and, following the tradition started by Henry David Thoreau, I announced I would do so publicly.

It turned out to be a lot harder to get arrested in San Francisco for civil disobedience than I thought.

Even so, we had a great time sitting in in front of Greenpeace and NRDC headquarters.

A few months later, in October, Environmental Progress, Mothers for Nuclear, and the Illinois chapter of the American Nuclear Society co-hosted a “Save the Nukes” meeting in Chicago to plot strategy.

This time, 18 people agreed to get arrested with me — that’s 17 more than had agreed to join me in San Francisco. Momentum was growing. I was inspired.

But after being lectured by EP’s general counsel about how different Chicago laws (and police) are from the ones in San Francisco, I canceled it.

At least the getting arrested part. In both Chicago and San Francisco, everybody wanted to sit down. And they wanted to do it together.

And we’re just getting started.

On June 12, I will have the great honor of giving a keynote lecture to the American Nuclear Society annual conference in San Francisco, where I will describe what must be done to save nuclear power, and the planet along with it.

A few days after, we will host another international gathering in our Berkeley headquarters.

And we will host another one in October, and as many more as it takes.

Nuclear energy is an area where there is has been far too much talk and far too little action. The subject has been analyzed to death.

The bottom line is that nuclear plants around the world that are being killed can be saved.

It won’t be easy or immediate, and there are no shortcuts. No technical fix or lobbying effort can overcome nuclear energy’s well-financed and well-organized opponents and the fears they sow.

Rather, anti-nuclear fear must be confronted directly, and exposed. This can and should be done in a truly civil way, backed by evidence, and with dignity. But it must be done if we are to save the only technology capable of ending poverty and reversing humankind’s negative impact on the environment.

These are dark times for pro-nuclear forces, but we are starting to see pinpoints of light. Pro-nuclear rebels are finding their courage, from California to Taiwan to Australia to Germany.

In three weeks many of us will meet for the first time, and learn about each other’s struggles. We will find ways to help each other in ways we can’t currently imagine.

We will discover that what we are seeking is truly universal — and beautiful: a world of nature and prosperity for all.